- Syllabus Home

- About #EmpireSuffrageSyllabus

- Modules

- Weeks

1: Empire and Universal Rights 2: Women and Revolutions 3: Documenting Race, Rights, and Family Ties 4: The Politics of Motherhood 5: "Civilizing Missions" and Voting Rights 6: The Struggle for Women's Suffrage in U.S. Colonies 7: Voting and Party Politics in the U.S. Empire 8: Case Study of When the "Empire Strikes Back": The Puerto Rican Diaspora 9: Nationalist Feminisms with Global Visions 10: Social and Economic Citizenship 11: Anti-Militarist Feminisms 12: Body Politics and Sexual Sovereignty 13: Women Who Ran 14: The U.S. Presidency and Gendered Political Culture 15: Global Women in Leadership

- Interactive Resources

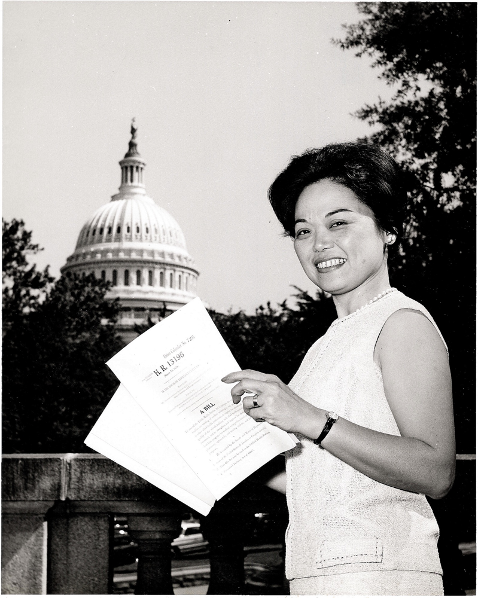

How have U.S. imperial and racial hierarchies shaped women’s desire to become president? Victoria Woodhull, who ran in 1872, promoted free love as well as eugenics. Margaret Chase Smith, a Republican and the first woman nominated for the presidency by a national party in 1964, is known for her 1950 “Declaration of Conscience.” She was the first senator to question the Cold War McCarthy witch hunts for suspected communists. Democrats Patsy Mink, the first Asian American woman legislator, and Shirley Chisholm, the first African American congresswoman, ran for the U.S. Presidency in 1972. They originated from islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean, respectively, and opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam and more broadly U.S. militarism. They also advocated for robust social programs to alleviate social inequalities in the U.S., many of them connected to the legacies of empire within the states and territories. Hillary Clinton—a former first lady, a senator, and a secretary of state—ran for the U.S. presidency twice in 2008 and 2016. She is known for promoting the feminist phrase, “women’s rights are human rights,” at the 1995 United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing as well as for her expansion of war and military intervention in the Middle East. What do the political careers and aspirations of these women who ran for the U.S. presidency reveal about the significance of U.S. empire in shaping gendered forms of citizenship and leadership? What were these women's goals in running for the presidency? What constitutes “success” or “failure” for these electoral runs?

Secondary Readings

In this 1999 work, Janann Sherman set out to write the first biography of US Senator Margaret Chase Smith. The author, who formed a close working relationship with Chase Smith and interviewed her many times over the course of developing this work focuses on Chase Smith’s relationship to her home state and the ways that her decades long career in the House and the Senate defied expectations of a congressional widow. Sherman argues that though Chase Smith first took office by filling the seat of her deceased husband Clyde Smith, her immediate interest in discussions of increasing military spending were representative of focused ambition and a clearly defined set of values. In chapters about Chase Smith’s appointment to the Naval Affairs Committee, her “Declaration of Conscience,” and the Cold War, the author continues to argue that Chase Smith's foreign policy defined her political career. The work also attempts to tease apart the many different media accounts of Chase Smith's poise and her notorious purse full of lollipops that she carried while meeting citizens in World War II ravaged-Europe as expressions of societal anxieties about women in politics. Despite the media scrutiny and the tight control of her administrative assistant, friend, and confidant William "Bill" Lewis on her public life, the book concludes that Chase Smith was able to maintain control of her public image and personal life through the 1972 election cycle and in her retirement years.

This article in E. James West’s series on 1968 presidential campaigns focuses on Communist Party candidate Charlene Mitchell, the first African American woman to run for executive office in the United States. In a brief biographical summary, West explains Mitchell’s journey from joining the Communist Party as a teenager in the 1930s to becoming one of the most influential leaders in the party by the 1960s through her active recruitment in Black labor unions. The author notes that Mitchell's Blackness and womanhood were both seemingly used as evidence by media outlets that the Communist Party was unable to put forth a serious candidate. Though her run was less public than that of Shirley Chisholm four years later, Mitchell’s 1968 campaign is important for understanding the rise in Black women in US electoral politics during the coming decade as well as the ways in which the “twin jeopardies” of race and sex made these campaigns difficult.

Brown, Nadia E., Sarah Allen Gershon, and Christina Greer. “To Be Young, Gifted, Black, and a Woman: A Comparison Between the Presidential Candidacies of Charlene Mitchell and Shirley Chisholm.” In Distinct Identities: Minority Women in U.S. Politics, 251–66. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.This chapter focuses on Charlene Mitchell’s 1968 run for presidency as a Communist and compares her run, its objectives and outcomes to those of other Black women who have sought the executive office. In the essay, Greer highlights the boldness of the campaign which was mounted only three years after the passing of the Voting Rights Act. Although Greer views Mitchell’s run as a form of protest politics, she also claims that it “helped pave a portion of the stony road” that Shirley Chisholm would embark on a few years later. Many women who worked on Chisholm’s campaign then went on to seek office, such as Congresswoman Barbara Lee. These positions are often the necessary prelude for women who seek the presidency such as Chisholm and later (as Greer correctly predicted) Kamala Harris, who ran in 2016. Harris’s run for the presidency was the first significant campaign for the presidency by an African American and multi-racial woman within the major parties since Chisholm's run in 1972, which represented the first significant campaign of an African American woman to run for election under either the major parties since Chisholm in 1972. Mitchell’s campaign was an important driver of future candidate ambition.

In this article, Wu examines the ways Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color to become a U.S. congressional representative, pursued anti-military and antinuclear policies as a representative of Hawaii. She used ideas about the interconnectedness of natural environments and life to argue against military experimentation and nuclear colonialism in the Pacific. Mink used political liberalism to fight for largely Indigenous peoples who were disproportionately affected by nuclear testing. Mink’s goals were not always entirely matched by Native Hawaiian activists, some of whom were more focused on Hawaiian sovereignty instead of inclusion in the U.S. empire. However, Mink’s political work was its own type of critique of the empire and was deeply informed by a Pacific worldview.

Wu, Judy Tzu-Chun. “Patsy Takemoto Mink blazed the Trail for Kamala Harris-Not Famous White Woman Susan B. Anthony.” The Conversation, 18 November 2020.This chapter traces Shirley Chisholm’s life and political career with a specific emphasis on how she was shaped by her Caribbean roots. She was influenced by the British imperial education she received in Barbados, which gave her a stronger understanding of colonial relationships. Her life in multicultural Brooklyn also allowed her to understand the diverse interests of her constituents, when she was a local and national representative. This chapter explores the way Chisholm’s femininity and race played a part in the challenges she faced as a politician and how she dealt with the twin difficulties of sexism and racism. This chapter does not shy away from some controversies, such as conflict between Caribbean and North American Black people in the 1960s and Chisholm’s statement that her femininity was more of a setback in gaining respect than her race.

Shirley Chisholm Project.This is a repository of resources about Shirley Chisholm and other grassroots activists in Brooklyn. It includes information about Chisholm as well as links to websites, videos, and other resources that could be useful for researchers.

Gallagher, Julia A. “Waging the ‘Good Fight’: The Political Career of Shirley Chisholm, 1953-1982.” Journal of African American History 92, no. 3 (Summer 2007): 393–416.This is a very straightforward account of Shirley Chisholm’s political career from when she first began participating in electoral politics in the 1950s to her retirement in the 1980s. Gallagher examines how Chisholm participated in political organizations, built political backing, conducted her campaigns, and worked to pass legislation. Gallagher also explores what kind of legislation Chisholm put forth (generally to benefit working-class women and minorities) and how successful she was at doing so. Gallagher analyzes what was successful and unsuccessful about Chisholm’s 1972 presidential campaign. This is a very in-depth analysis of politics above all else, but it is a short article that gives a good summary of Chisholm’s political accomplishments.

In the chapter “Hillary Clinton’s Candidacy in the Historical and Global Context,” author Susan M. Hartmann considers the ways that Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential run fit within and departed from the patterns of U.S. women in political office. The author explores the commonalities between Clinton’s career and those of other women in Congress, such as Margaret Chase Smith and Miriam A. Ferguson, who were strongly associated with the political careers of their husbands. Hartmann also compares the campaign to those of other women who dared to run for president, such as Patsy Takemoto Mink and Shirley Chisholm. The chapter posits that Clinton’s campaign was primarily distinct from prior presidential runs in terms of scale and intent. No other female candidate had stood so close to winning the nomination. Hartmann also reminds us that no other female candidate had so explicitly run to win.

Fitzpatrick, Ellen. The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women's Quest for the American Presidency. Harvard University Press, 2016.This work about three pathbreaking female candidates for president—Victoria Woodhull, Margaret Chase Smith, and Shirley Chisholm—is bookended by discussions of the 2008 and 2016 presidential campaigns of Secretary Hillary Clinton. Throughout the text Fitzpatrick uses the careers of these women to interrogate common behaviors in the candidates as well as in their detractors. Fitzpatrick argues that each of these women ran with the purpose of furthering the chance of women to win the nomination of a majority party and to be elected to executive office. Each of these campaigns was plagued with challenges relating to the gender of the candidates, including disproportionate media attention to the women's physical appearances and tones of speech compared to those of male candidates. The work also includes biographical summaries of the women’s lives leading up to their respective decisions to enter political life.

Featherstone, Liza. False Choices: The Faux Feminism of Hillary Rodham Clinton. Brooklyn: Verson Books, 2016.This recent collection of essays, edited by Liza Featherstone, is grounded in discussions of the foreign and domestic policies of former U.S. senator, secretary of state, first lady, and 2016 Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency Hillary Clinton. The authors analyze Clinton's politics in contrast to her oft-repeated 1995 declaration that “women’s rights are human rights.” An introduction to the collection, written by Featherstone along with Amber A’Lee Frost, foregrounds how Clinton’s public emphasis on the rights of women and children is directly problematized by her record of dealing with issues such as poverty, crime, and terrorism.

The collection is divided into sections on foreign and domestic policy, named “Hillary at Home” and “Hillary Abroad.” Part 1 provides necessary context to Clinton’s foreign policy. Essays such as “Neoliberal Fictions: Harper Lee, Hillary Clinton and My Dad” as well as “Clinton’s War on Drugs: When Black Lives Didn’t Matter” analyze how her policies are consistently shaped by an embodied sense of American exceptionalism. A key essay by Yasmine Nair uses the term “carceral feminism” to refer to the ways in which Clinton uses justice for women as justification for carceral punishment in both her hawkish approaches to US intervention and in her tough-on-crime stance in American cities. Essays in section 2, such as Bélen Fernanández’s “Hillary Does Honduras” and Medea Benjamin’s “Pink Slipping Hillary Directly," confront the lasting consequences of Clinton’s foreign policy in the Middle East and Latin America as experienced by women and children.

Richards, Rebecca S. “Cyborgs on the World Stage: Hillary Clinton and the Rhetorical Performances of Iron Ladies,” Feminist Formations 23, no. 1 (2011): 1–24.The author argues that women who hold positions as heads of state reveal how Donna Haraway’s cyborg ontology functions within political reality. A key question in the work is whether women must transform into iron ladies to enter masculine political spheres. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton exemplified the strategic performance of steeliness in her campaign during 2007 and 2008, a strategy of becoming and transforming through the technological means described by Haraway. Richards concludes that cyborgian identities are dangerous roles for women to play, because such roles are as likely to ensnare them as to obscure the limitations of running for political office as a woman.

Primary Sources

In 1950, 14 years prior to her campaign as the first American woman to run for the U.S. presidency with the endorsement of a major political party, U.S. Senator Margaret Chase Smith delivered this denouncement of McCarthyism to the Senate. In her speech, Smith emphasized her role as a woman and a Republican as she declared the Cold War practices of her party as having been more influenced by political opportunism than genuine Republican values. The eponymous “Declaration of Conscience” refers to five-point declaration of Republication principles with which she concludes. In this directive she implores her fellow Republicans to identify first as Americans, to not mimic the Democratic administration in their exploitation of the fear and confusion of the American people, and to prioritize national security while focusing on individual freedoms.

This is a collection of primary documents related to Chisholm’s political career and contains letters, speeches, newspaper articles, flyers, legislation, and public statements. While these documents come from all points of her political career (New York assemblyperson and U.S. congressperson), two documents of particular interest to her presidential run are her Statement of Candidacy (Document 13), and her Presidential Campaign Position Paper No. 5 (Document 14B). Her statement of candidacy outlines generally what her goals as a president were and briefly addresses both her race and gender. Her position paper addresses timely topics such as prison reform, police brutality, and civil rights.

This is the text of Clinton’s speech at the World Conference of Women that was held in China in 1995. She famously declared “human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights,” thus aligning women’s rights more completely with the worldwide human rights cause. She also highlighted efforts of women to unite and create better health, labor, economic, educational, and political situations for themselves. At the same time, she drew attention to violations of women’s rights globally, including in the US and China, which some people viewed as a move in global statecraft on her part.

This article written around the time Hillary Clinton received the Democratic nomination for president details other women who ran before her. The women discussed include Victoria Woodhull, Margaret Chase Smith, Shirley Chisholm, Patsy Takemoto Mink, Pat Shroder, and Carol Moseley Braun. The article illustrates not only the challenges for women running for president at different points in history but also the remarkable achievements of the women who ran. This is a good companion piece to this section’s timeline.

(See also “Before Her Assassination, Berta Caceras Singled Out Hilary Clinton for Backing Honduran Coup.” Democracy Now.)

This article published the week of Berta Cáceres’s murder, which occurred on March 3, 2016, explores the deceased activist’s claims that Hillary Clinton legitimized the 2009 coup in Honduras and was responsible for a subsequent wave of political murders in the country. The article cites a 2014 video interview in which Cáceres admits that she feared assassination and named Clinton as responsible for the criminalization of political protest. The author also discusses Belén Fernández’s essay “Hillary Does Honduras,” which provides an account of Clinton's erasure of mentions of the coup from later editions of her memoir Hard Choices.

Videos

A 76-minute documentary that traces Chisholm's presidential run that includes interviews with academic scholars and Shirley Chisholm herself shortly before she died. It also includes news footage from the 1970s. Currently (2020) available on Amazon Prime.

This is a 56-minute documentary that follows the life and political career of Patsy Mink from her childhood in Hawai‘i to her run for president and push for Title IX legislation as a congresswoman in Washington D.C.

This is a two-minute video consisting of clips of speeches and interviews that Shirley Chisholm gave during her presidential campaign. A running transcript of these speeches is also included.