Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890-1920

Biography of Louise Hall, 1881-1966

By Elisa Miller, Associate Professor of History, Rhode Island College and Scott Vehstedt, Independent Historian

Annie Louise Hall was born on the American naval base in Pensacola, Florida on January 15, 1881 to Martin Ellsworth Hall and Mary (Cushing) Hall. Her father was a lieutenant in the United State Navy and earned the rank of commander. Both sides of Hall's family had historic roots. Her mother's family had descendants who came on the Mayflower in the early 1600s; her father's family arrived in the Massachusetts Colony in the 1600s. Her paternal great-great grandfather, Oliver Ellsworth, was a member of the Continental Congress during the American Revolution and the Constitutional Convention in the 1780s. In the new republic, he served as the first U.S. Senator from Connecticut and the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Martin Hall served in the Spanish-American War as part of the navy. By 1884, Martin Hall had been transferred to the Newport, Rhode Island naval base and the family lived there. They remained in Newport until 1891 and by the 1900 U.S. Census, they had moved to Lowell, Massachusetts where they lived with Cushings, the mother's family.

Louise Hall attended Vassar College and graduated with an A.B. degree in 1903. Her older sister, Margaret Woodburn Hall, also attended Vassar College. After graduating, Hall worked as a teacher for several years. She first was a teacher at the Bardwell School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she taught algebra, Latin, and French from 1903-1905. In 1905, she took a position in Cleveland, Ohio at Miss Mittelberger's School teaching math and science. Hall told her former Vassar classmates that she was "teaching in the cellar of Miss Mittelberger's School, doing my best to burn up the building with all sorts of chemical explosives." The following year, she moved to Buffalo, New York and taught chemistry and math at the Buffalo Seminary until 1908. During her teaching career, Hall spent several summers advancing her scientific education in biology, physics, and chemistry at the Woods Hole Biological Laboratory and the Harvard Summer School. Later in her suffrage career, Hall worked as an organizer in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York, states where she previously had worked as a schoolteacher. In 1908, Hall left teaching and worked as a reformer in a settlement house in New York City. For one year, she was a settlement house reformer for the Normal College Alumnae House living and working on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with immigrants from Czechoslovakia. As she explained in a Vassar College alumnae bulletin, she was "leading a fascinating Bohemian life on the east side of the Metropolis. The community in which I live in is Bohemian in race as well as character, and many of the women do not speak a word of English." By 1910, she had moved back to her family home in Lowell, Massachusetts and was working as a secretary at a mining company.

Hall connected her interest in the movement to her work as a settlement worker in New York in 1908-1909. She said that while living and working with poor immigrants, that she saw many "abuses and bad conditions...[that] had remained for years although they had been called time and again to the attention of the officials." When the women reformers became aware of these problems, they also complained to officials but they "had not been able to secure any action because they did not have votes to back up their demands." Hall said that her first activity for suffrage was in New York in either 1908 or 1909 when she signed a petition for the New York Legislature about woman suffrage. The refusal of the Legislature to take action, she explained had "converted her and she decided that it was time to join the [suffrage] crusade." Later in her career, she summed up her philosophy about woman suffrage succinctly as "women are people and this is the whole question in a nutshell."

While living in Massachusetts, Hall became an activist in the suffrage movement. From this beginning, Hall developed a career as a suffrage organizer for state suffrage associations in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Connecticut, and New Hampshire from 1912 to 1918. In the beginning of her suffrage work in Massachusetts, Hall took part in a wide variety of activities. In 1910, the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) conducted a state-wide house-by-house canvassing campaign for woman suffrage. Hall was in charge of a ward that included Lowell; she also served as the director of a MWSA auxiliary league in Lowell. She attended an "aero meet" in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1911 with a group of suffragists. At the airplane demonstration, the suffragists came "in a large touring car which was gaily decorated with votes for women flags and immense placards announcing the mass meeting on Boston Common. They sold California poppies and votes for women buttons and gave out thousands of cards announcing the big meeting." In Massachusetts, she developed skills as a public speaker for suffrage that she later put to use in suffrage campaigns in numerous states. In November 1911, she took part in a week-long suffrage campaign in Boston at the Bijou Theatre, with suffragists Maud Wood Park and Florence Luscomb. Hall gave two speeches on woman suffrage daily in between movie showings at the theatre.

Based on her work in Massachusetts, in the beginning of 1912 the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association and the Rhode Island College Equal Suffrage League hired Louise Hall to be their field secretary. She was the first paid suffrage organizer in Rhode Island. Hall ultimately worked in Rhode Island for only three or four months before moving on to other campaigns. Despite this short tenure, Sara Algeo, a prominent Rhode Island suffragist, described Hall in her memoir as being "a distinct step in advance" for the Rhode Island suffrage movement. She helped the Rhode Island organizations develop new tactics to increase awareness and support for suffrage.

At the first suffrage meeting she attended in Rhode Island in February 1912, Hall gave an address in which she explained the kinds of strategies that she thought were effective. The Providence Journal quoted her as saying that:

Some of the most effectual means in her own experience were parlor meetings, to reach the leisure women; personal solicitation from house to house for the women in the homes; noon meetings for those in the factories and shops, and large meetings for professional women. She told of the success of a stereopticon entertainment at which lantern slides were exhibited which dealt with the progress and reasonableness of the suffrage questions and alleged it had the double advantage of appealing to the eye as well as to the ear of the public.

She held daily luncheon meetings about woman suffrage in downtown Providence for factory workers. Hall arranged for the suffrage organizations to have a booth at the Pure Food Exposition in Providence, an annual event that the suffragists continued throughout the 1910s, reaching thousands of Rhode Islanders. She filled the booth with suffrage cartoons, posters, literature and novelties that were on display and for sale. Louise Hall also held the first open-air suffrage rally in Rhode Island in downtown Providence on April 11, 1912. The Providence Journal ran a photograph of Hall giving a speech standing on a peanut box to a large crowd and described her as "dressed in a smart walking suit of brown, and holding a large yellow flag on which appearing the lettering, 'Votes for Women'" and explaining "the cause from diverse angles of arguments." Besides her speech, Hall and two other suffragist carried bags that read "Votes for Women," sold suffrage buttons and copies of The Woman's Journal suffrage publication, and passed around a large yellow sign advertising an upcoming Providence speech by NAWSA president, Anna Howard Shaw.

In a feature story about Hall in The Providence Journal, she explained some of her theories about being a suffrage activist. She estimated that there were only around 25-30 professional suffrage organizers in the United States and that was a difficult profession to figure out. She said:

There aren't any textbooks for suffrage workers. There are pamphlets, of course, discussing various method, but nothing like a guide to the profession. When I began 18 months or so ago, the workers in Boston told me how to go about it, with the different methods of work. But what will do in one place won't in another. The first thing is to study the field, see what is most likely to be effective and then develop your methods as you go along.

Hall explained that the most important element of being a professional suffragist was "devotion to the cause and a little common sense."

Her work in Massachusetts gave her experience in trying different tactics. She said, "The first thing to do is to get an audience. The suffrage worker will do anything to accomplish that. It all depends on local conditions whether it is best to take to the street corners or to secure a hearing at indoor meetings." She said that going door to door could be challenging and that it was "not always pleasant, of course. Once in a while a woman slams the door in our faces. But as a rule they at least give us a hearing. Even the rebuffs never bothered me. There's usually a funny side to them, and the suffrage worker shouldn't be too serious." She talked strategically about seeking out the richest and most influential people in town and trying to secure their support, as well as the importance of reaching out to men in addition to women. Hall also developed strategies to reach women who were wary of the suffrage movement and explained that she started "sending out notices on which I expressly stated that attendance at the meeting would not imply adherence to the cause, but merely a willingness to hear one side of an important public question. Since then I have used that on all notices I have sent out."

In her ideas about strategies for the suffrage movement, Hall rejected the more radical tactics of the British movement. In a newspaper interview, she said that that unlike British suffragettes, such as the Pankhurst sisters, that she had never smashed plate glass windows and that that tactic "isn't necessary over here." When Emmeline Pankhurst planned a visit to the United States in 1913, Hall made it clear to newspapers that the American suffrage associations did not support militant methods.

Although Hall developed a reputation as a captivating and effective public speaker, she confessed that giving speeches at the open-air meetings gave her stage fright that felt like "the preliminary stages of accidental drowning in ice water." She continued, though, "It's only the first minute or so while you're talking to empty space with a few idlers across the street who begin to laugh. After to get somebody to come up near enough to hear what you're saying it is easier. But you surely do feel foolish at the start."

By May 1912, NAWSA requested that Hall and Mrs. Camillo von Klenze, president of the Rhode Island College Equal Suffrage League, assist in a suffrage campaign in Ohio. The state of Ohio had a public referendum for an amendment to the state constitution granting women's suffrage scheduled that fall and suffragists were waging a strong campaign in support of it. Prominent suffragists who participated in the Ohio campaign included Rose Schneiderman, Jeannette Rankin, Maud Wood Park, Laura Clay, Anna Howard Shaw, and Harriot Stanton Blatch. Hall spent much of her time in Ohio partnered with Susan Fitzgerald from Massachusetts. Sara Algeo noted of Hall and von Klenze that, "We could ill spare them [in Rhode Island], but gave them our blessing and God speed for the place where they were needed most."

As in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, in Ohio Hall took the lead in numerous activities to advance the cause. Hall showed a willingness to try new tactics to get the message out. In Akron, Hall became the first woman in the county to ride in an airplane and dropped suffrage pamphlets from the air. The newspaper noted that she was scheduled to give a speech after the plane ride, "IF SHE GETS DOWN ALIVE!"

One incident that brought her media attention involved the Buffalo Bill and Rough Riders show. Hall explained that she climbed over fences, a railroad, and hill in order to get behind the scenes. She said:

I found myself in with Buffalo Bill and his cohorts, all lined up on horseback, ready to ride into the ring. Nearly every man carried a banner, German, English, American, etc. I offered Buffalo Bill our 'Votes for Women' flag that followed Taft and Teddy. He handed it over to one of the racers, and round the ring it tore three times...Each flag was greeted with cheers, but the Stars and Stripes and votes for women came in for the loudest cheering.

Newspapers noted that Hall and Fitzgerald were "publicity experts in drawing attention" to the suffrage meetings in Ohio, using amusing banners to gain attention. They credited Hall with creating the "circus campaign" which involved getting suffrage banners in circus parades. One newspaper report described Hall standing up in a car with a flag and megaphone as she sped through the streets of Cinncinati as giving "one the impression of the angel with the trump in the chariot, 'comin' from to carry me' to the voting booth."

Hall gave many speeches in towns and cities across the state for several months. In Cleveland, Hall and Rose Schneiderman organized daily talks at noon for factory workers. Hall gave speeches on woman suffrage and topics related to workers, such as "the drift of women's work from the home to the factory." Often in her speeches, Hall tried to counter arguments against women voting. A common argument was that politics and voting would undermine their roles in the home. Hall's speeches frequently drew on maternalist ideas—that women think, feel, and act differently from men and that these differences would make them moral and nurturing as voters, benefiting politics and American society. As she explained, "men are coming to realize the government needs certain feminine attributes." At a speech in Hamilton, Ohio, Hall told the audience that, "The woman in the home needs the vote as much as any other class of women, in order to look out for the interests of the home, to manage her home properly and make it minister to the needs of her husband and children." She continued that home life had changed with industrialization and that:

that the conditions of life as they existed half a century ago when each family was the center of its own home industries has changed, and these things have been taken over by the government—the methods of supplying the home with food, with clothing and the other necessities of life, and in order to look out for these interests of the home women must go into politics.

In her speeches, Hall often quoted noted educator and suffragist Sophonisba Breckinridge as saying "Housekeeping and homemaking have become public functions, and therefore the ballot is a domestic necessity."

Ohio was a heavily industrialized state and Hall stressed the importance for women factory workers and the poor to have the right to vote. She mentioned the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire that killed almost 150 young women workers as evidence of why working women needed the vote to improve working conditions. Hall claimed "the poorer women know the short comings of the government and that the ballot is their only means of protection." Hall also emphasized that woman suffrage was a necessary component of democracy. In Akron, Ohio, Hall spoke for 90 minutes on a street corner to an audience of 1000. The Akron Beacon Journal quoted her as stating that "the nation was not a democracy because all did not vote and thus all were not represented."

Hall's speeches reached thousands of listeners and garnered much attention by newspapers. In an article from the Eau Claire Sunday Leader, Edna K. Wooley described Hall as looking nondescript and ordinary in appearance, "but when one saw this woman standing upon a little stone speaker's platform in the Public Square of a big city with a great yellow banner...while she talked to a large crowd of men who listened silently, thoughtfully and respectfully—well, one simply had to stop and take notice."

The Woman Suffrage Party of Cleveland wrote to The Woman's Journal about the Ohio constitutional campaign. The letter praised Hall's contributions to the campaign:

Miss Hall, Rhode Island's invaluable donation to the cause of suffrage for Ohio, was doing wonderfully effective and constructive work. Daily during her stay here she held open-air meetings outside of factories and in the public square. Always accompanied by two or three of our younger members, who dispensed literature, Miss Hall reached thousands of voters during her stay here. Our gratitude to her and to Rhode Island is deep and sincere.

Following several months working in Ohio, Hall returned to Massachusetts. The suffrage referendum in Ohio failed in the fall.

In Massachusetts, Hall worked as executive secretary School Voters League in Boston. The organization worked to educate voters on issues related to the schools, such as teacher pay and class size and to try to get a woman appointed to the school board. She also resumed her suffrage work, including participating in an auto tour with Susan Fitzgerald using megaphones and bugles to wake up residents and draw their attendance to an upcoming suffrage rally. Hall attended the 1912 NAWSA convention in Philadelphia. She gave an address at an outdoor suffrage rally at Independence Square that also featured speakers including Alice Paul, Anna Howard Shaw, and Harriot Stanton Blatch. The History of Woman Suffrage described this event as a "great out-door rally in Independence Square...such as had been witnessed many times on this historic spot conducted by men but never before in the hands of women." In March 1913, NAWSA put on a high-profile suffrage parade in Washington, DC timed to coincide with Woodrow Wilson's presidential inauguration. Hall attended the protest and was scheduled to give a speech at it.

In April 1913, Hall returned to full-time, paid suffrage work and moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where she had been hired as executive secretary of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA). As executive secretary, Hall handled administrative tasks for the PWSA, held meetings, gave speeches, and helped establish new suffrage branches throughout Pennsylvania. Hall wrote to the Vassar alumnae bulletin about her new position, stating that she was "ready to welcome the co-operation of all 1903 [Vassar] Pennsylvanias in making the Keystone State a Government of the People, For the People and By All the People in November, 1915." By April 1914, the PWSA changed Hall's position from executive secretary to organizing secretary, in order to allow her to more time doing suffrage activism in the field and less time on administrative work in the office.

As organizing secretary in 1915, Hall embarked on an ambitious and dramatic suffrage campaign in Pennsylvania. In the November 1915 elections, the state of Pennsylvania had a referendum on woman suffrage on the ballot. In order to drum up support for the referendum and woman suffrage, Hall and a handful of colleagues established the "Woman's Liberty Bell" tour with Hall serving as director and chief spokesperson. PWSA member, Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger paid $2000 for a replica of the Liberty Bell, except for without the famous crack and with its clapper chained to represent women's lack of political rights. Hall supervised a five-month campaign in 1915 in which the group of suffragists and the 2000-pound bell, carried on a specially-built truck driven by Hall's brother, Oliver, traveled 5000 miles to all sixty-seven counties throughout Pennsylvania. Hundreds of thousands turned out to see the bell and hear Hall's speeches on woman suffrage during the campaign, with 75,000 attendees estimated in Western Pennsylvania alone. The tour received extensive coverage in local and national newspapers. In October, two weeks before the referendum, the bell arrived in Philadelphia for a suffrage parade that The New York Times stated had 8,000 marchers and an audience of 100,000 people.

Hall explained the symbolism of using the bell for the woman suffrage tour. She said:

[The Liberty Bell] stands as the sacred symbol of all the glorious ideals which have made our nation possible. In casting the Woman's Liberty Bell, we have only made a huge bronze tribute to the memory of the old bell and the ideas it stands for. The message that the Woman's Bell is to peal forth when the women of Pennsylvania are granted the right to vote will not actually be a new one. It will merely be the completion of the original bell's message—'Proclaim liberty throughout the land to all the inhabitants thereof.'

In addition to her usual themes about maternalism and industrialization, Hall drew heavily on the symbolism of the bell and the American Revolution in her speeches on the tour. In one speech she proclaimed that "We women were left out of the original bell's message...If taxation without representation was tyranny in 1776, isn't it just as much tyranny today to tax women for the support of a government in which they are given no voice?" She urged male voters in Pennsylvania to vote for the suffrage referendum in November so that the woman's liberty bell "will be able to ring out the glad tidings of political liberty for our women and the Keystone State will have the proud distinction of being for the second time in history a cradle of liberty."

As she had demonstrated throughout her career, Hall was a dynamic speaker for woman suffrage on the campaign. Local newspapers consistently praised her speaking abilities. At a stop in State College, Pennsylvania, the newspaper reported on a speech she gave to a farmers' organization. The article stated that, "Miss Louise Hall, of Harrisburg, stood in her automobile...and sent out her message. So large was her audience that it was impossible for those on the outskirts to hear the speaker. Virtually every person on the grounds was in the crush about Miss Hall's machine." In Carlisle, Pennsylvania, an article noted that her "charming personality, quick and eloquent tongue, and strong, musical voice, make her an ideal speaker and even the most lukewarm audience catches the contagion of a good cause advanced by a magnet." A Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania paper called Hall "easily the most popular suffragist in Pennsylvania today, and her quick wit and charming personality can be credited with the winning of innumerable converts." It went on to describe a speech that Hall gave on the street in a heavy rain without an umbrella in which she "held a large crowd of men in delighted attention to the close of her speech." Yet another paper in Northumberland, referred to her as "a brilliant speaker" who "punctured all the stock arguments against votes for women in a clever and convincing manner."

One of Hall's colleagues on the Liberty tour was Elizabeth McShane, who was also a Vassar alumna, a 1913 graduate. McShane recounted that she joined the campaign at Hall's urging when the tour came through her home town in June 1915 and that "Louise was a wonderful speaker...We campaigned over much of Pennsylvania, mostly on dirt roads." Hall and McShane marched on a Philadelphia street wearing sandwich boards, that included messages such as: "Do Women Want the Vote? Six hundred thousand organizations, with 50,000,000 members have indorsed woman suffrage!," "Pennsylvania's last chance November 2 to be one of the 13 original suffrage states. Are you going to help?," and "If women vote, must they fight? Fifty per cent of men who vote are not fit for the army or navy. Since women bear soldiers, they should not be expected to bear arms."

Despite the liberty bell tour and the suffragists' efforts, the constitutional referendum on woman suffrage in Pennsylvania failed in the November election. McShane explained that the defeat, led her "to abandon the effort to get the vote State by State and join the efforts of Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, leaders of the Congressional Union...to have Congress ratify a national amendment." In the following years, McShane became a supporter of Alice Paul's National Woman's Party and took part in high-profile and controversial protests at the White House during World War I but Hall remained active in NAWSA state organizations.

Another woman who assisted Hall on the Women's Liberty Bell tour was Ethel Bret Harte, daughter of the author Bret Harte. The two became life partners and were involved in a close relationship for at least fifty years, although Hall referred to Harte as her "house-mate" in alumnae reports. It is not clear when or how Harte and Hall first met. In the years following the liberty bell tour, Hall and Harte lived in separate states but occasionally traveled together in the United States and Europe. In the 1930s, though, they travelled across the country, built a house in Ojai, California, and lived together until their respective deaths in the 1960s.

As World War I broke out in Europe, Hall connected the issue of war to woman suffrage. She again highlighted the idea that women would bring different and beneficial traits to politics. The Altoona Tribune cited her as claiming that "Women suffer the most from war, hence if they could vote, their political opinion would naturally be against it and [war] would, in all probability, be averted." In another speech she stated that "women should have a voice in saying whether or not the nation should go to war, since they, above men, appreciate the cost of human life."

Once the United States entered the war in 1917, NAWSA encouraged women's war voluntarism as a strategy to increase support for woman suffrage due to the demonstration of women's patriotism and citizenship. Hall participated in this kind of war work. During the war, in addition to her addresses about woman suffrage, she gave speeches about the American Liberty Loans, to raise money for the war effort. In an update to the Vassar alumnae, she noted that, "As for war work—I have never knit a sock, but I can do sweaters and helmets." The more militant National Woman's Party held protests at the White House during the war hoping to put pressure on and embarrass President Wilson. Hall, though, believed that the possibilities for success of woman suffrage were promising because Wilson had voted for woman suffrage in his home state of New Jersey during a failed state constitution referendum there in 1915.

By 1917, Hall was a field secretary for the New York Woman Suffrage Association. There was a woman suffrage referendum to the New York constitution on the ballot in the November election and she gave speeches throughout the state trying to get voters to support it. In these speeches, she connected World War I to woman suffrage. Hall declared that "the men who fight in France to make democracy safe are not going to refuse to make the Empire State a real democracy, in the face of the splendid work which women everywhere are doing" and that "I believe women will win the vote in New York this fall just as much as I believe we shall win this war with Germany." Unlike the previous state campaigns for woman suffrage that Hall had worked on in Ohio and Pennsylvania, the New York one was successfully passed by voters in 1917. Following the woman suffrage victory, Hall worked on Americanization programs in New York, in response to increasing xenophobia during the war and to alleviate concerns about foreign-born women getting the right to vote. She also participated in voter education efforts, giving addresses about the process of elections and government functions.

By mid 1918, Hall was working as a suffrage organizer in Connecticut, a state in which her Ellsworth family had deep historic roots. She was only in Connecticut briefly before the NAWSA leadership requested that she go to New Hampshire in the fall of 1918 to work on an important suffrage campaign there. There was a senatorial campaign going on in New Hampshire where the current governor, George Moses, was running for the Senate and had expressed his opposition to the woman suffrage constitutional amendment. One senator's vote might be enough to pass or defeat the amendment in the Senate. NAWSA needed Hall and other suffragists worked in New Hampshire to defeat Moses and elect the pro-suffrage candidate, John B. Jamieson. Despite their efforts, Moses narrowly won the election amidst allegations of voting fraud, and Hall sent NAWSA president, Carrie Chapman Catt, a telegram the next day updating her about the status of the election. Hall's work in New Hampshire at the end of 1918 appears to be the last work she did as a suffrage organizer. She returned to Lowell, Massachusetts and focused on a new career in business.

In addition to her suffrage activism, starting in 1916, Hall had begun a side career as a saleswoman. From 1918 to 1932, Hall worked for Mass Mutual Life Insurance in Boston and lived in Lowell, Massachusetts with family members. She connected her work in financial services to women's rights. In a 1917 report to Vassar alumnae, Hall explained that she was selling bonds and annuities and that although it was "a comparatively new field for women, the work is interesting and offers unlimited opportunities for helping women to learn to save systematically and to manage their own affairs without the too often deplorably speculative assistance of their nearest male relatives." She was later appointed supervisor of the woman's department at Mass Mutual.

Outside of her business career, Hall became active in numerous clubs and hobbies. In the 1920s, she took up hiking and mountain climbing, including trips to the Canadian Rockies and the White Mountains in New Hampshire, and was a member of the Appalachian Mountain Club. She also belonged to the Women's City Club of Boston, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, the New England Anti-Vivisection Society (an organization against medical experimentation on animals), and the American Theosophical Society (an organization dedicated to religious, scientific, and philosophical inquiry).

Hall visited Ojai, California around 1928 during what she called a "sabbatical year," in "a quest for change and adventure." By 1934, Hall and her partner decided to move to Ojai. As Hall explained, "Ethel Brete [sic] Harte and I bought a car and drove across the continent and built ourselves a little bungalow in the beautiful Ojai Valley in Southern California—that famed old people's paradise where we planned to toast our ageing bones till called to its heavenly counterpart." They soon became frustrated with the region's lack of seasons, greenery, and mountains and longed for New England; they ended up keeping the home in Ojai until their deaths in the 1960s but spent periods living in New England.

Hall remained active politically into her seventies. On her 1960 alumnae report, she reported that she was working to "get capital punishment abolished and Adlai ticketed for the Democratic presidential nomination." Louise Hall died in Ojai, California on September 20, 1966 at the age of eighty-five years old. Ethel Bret Harte had died in Ojai two years earlier in 1964.

Louise Hall speaking in Providence, RI (1912). Sara M. Algeo, The Story of a Sub-Pioneer (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham Co., 1925), 128.

"Women Urge Vote in Open-Air Talk," The Providence Sunday Journal, April 14, 1912. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, RI.

"How'd You Like to Make a Business out of 'Suffraging'?," The Providence Sunday Journal, March 31, 1912. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, RI.

Miss Louise Hall with brush and Miss [i.e. Mrs.] Susan Fitzgerald assisting bill posting in Cincinnati. 1912. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001704187/.

"Hurrah For Ohio!," The Woman's Journal 43, No. 23 (June 8, 1912), 177. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Suffraget Will Ride in Aeroplane," The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, OH), July 30, 1912

"Suffragists on Auto Tour Wake Suburbs," The Boston Globe, January 24, 1913.

Louise Hall Speaking from the Back of the Vehicle Holding the Liberty Bell and a "Votes for Women" Banner during a Suffrage Campaign Stop in Pennsylvania. (1915). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Louise Hall Speaking Outdoors to a Crowd of Men, Perhaps Workers from Area Businesses, during a Stop on the Pennsylvania Suffrage Campaign. (1915). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"How'd You Like to Make a Business out of 'Suffraging'?," The Providence Sunday Journal, March 31, 1912.

"Addresses Mine Workers," The Wilkes-Barre Record (Wilkes-Barre, PA), July 22, 1913.

"Votes for Women Advocated in Farmers' Institute Address," The York Daily (York, PA), February 9, 1914.

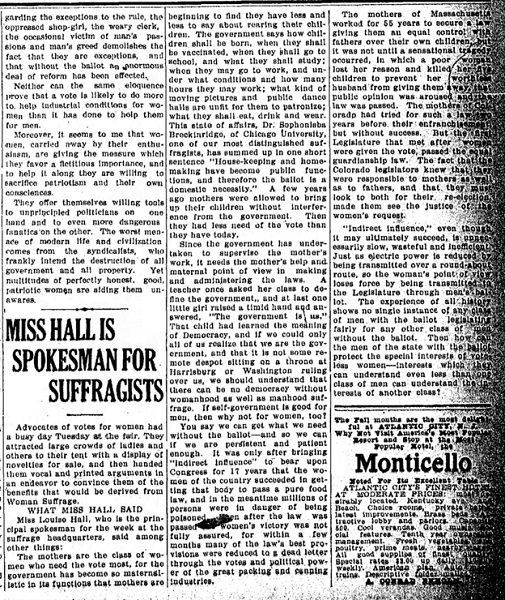

"Miss Hall is Spokesman for Suffragists," The Lebanon Daily News (Lebanon, PA), August 19, 1914.

"Suffrage Campaign in Blair County Will Start on Sept. 17," The Altoona Times (Altoona, PA), September 16, 1915.

Sources:

Ida Husted Harper, ed. The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 5: 1900-1920 (New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company, 1922), 333. [LINK].

Ida Husted Harper, ed. The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 6: 1900-1920 (New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company, 1922). In Pennsylvania [LINK] and Rhode Island [LINK] chapters.

Sara M. Algeo, The Story of a Sub-Pioneer (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham Co., 1925).

Vassar College Alumnae/I Biographical Files, Vassar College Archives & Special Collections Library, Poughkeepsie, NY.

Vassar College Class of 1903 Records, Special Collections Library, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY.

Holly Jean Holst, "Silent No More: The Justice Bell," The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/liberty-bell/justice-bell/.

"The Justice Bell Story," Justice Bell Foundation. https://www.justicebell.org/the-justice-bell-story.

Melissa Callahan, "Commemorating the Justice Bell Tour," Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities, Rutgers University-Camden. https://march.rutgers.edu/commemorating-the-justice-bell-tour/.

Dale Mezzacappa, "Vassar College and the Suffrage Movement," Vassar Quarterly 69, No. 3 (March 1, 1973), 2-9. https://newspaperarchives.vassar.edu/?a=d&d=vq19730301-01.2.7&

"Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association," The Woman's Journal 42, No. 4 (January 28, 1911), 27. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Bay State Work," The Woman's Journal 42, No. 34 (September 2, 1911), 278. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Plans Laid," The Woman's Journal 42, No. 42 (November 4, 1911), 351. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Five A Day," The Woman's Journal 42, No. 44 (November 18, 1911), 367. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Hurrah For Ohio," The Woman's Journal 43, No. 23 (June 8, 1912), 177-178, 184. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Great Doings In Ohio," The Woman's Journal 43, No. 20 (May 18, 1912), 158. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Keystone State Outlines Plans," The Woman's Journal 44, No. 30 (July 26, 1913), 238. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Granges Come As Christmas Gifts," The Woman's Journal 44, No. 52 (December 27, 1913), 409. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"News Notes," The Woman's Journal 45, No. 39 (September 26, 1914), 263. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Liberty Bell Starts On Way," The Woman's Journal 46, No. 27 (July 3, 1915), 212. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

"Suffrage Body Meets," The Providence Journal, February 6, 1912.

"Work for Equal Suffrage," The Providence Journal, February 14, 1912.

"Suffragettes Hear An Address by Miss Hall," The Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe, OH), July 15, 1912.

"In Social World," The Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe, OH), July 17, 1912.

"Big Suffrage Meeting," Hamilton Evening Journal (Hamilton, OH), July 12, 1912.

"Suffraget Worker Speaks to Large Akron Audience," The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, OH), July 29, 1912.

"Suffraget Will Ride in Aeroplane," The Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, OH), July 30, 1912.

"The Newest Record for Suffrage Campaigning," Buffalo Sunday Morning News (Buffalo, NY), August 25, 1912.

"Fighting the Women's Battle in Ohio," The Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, PA), September 5, 1912.

Edna K. Wooley, "The Woman in the Public Square," Eau Claire Sunday Leader (Eau Claire, WI), October 27, 1912.

"In Miss Hall's Honor," The Boston Globe, April 16, 1913.

"Suffragist Says Militancy Not Desired Here," The Pittston Gazette (Pittston, PA), September 8, 1913.

"Aid for Suffrage Parade," The Chicago Tribune, January 7, 1913.

"Suffragists on Auto Tour Wake Suburbs," The Boston Globe, January 24, 1913.

"Miss Hall Manager for Suffragists," Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, PA), April 26, 1913.

"Miss Hall to Devote All Her Time Now to Organizing," Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, PA), April 10, 1914.

"Suffrage Notes," Altoona Tribune (Altoona, PA), April 14, 1915.

"Suffrage Bell is Coming Next Week," Altoona Tribune (Altoona, PA), June 30, 1915.

"Woman's Liberty Bell Greeted in Meadville," The Evening Republican (Meadville, PA), July 1, 1915.

"Liberty Bell Greeted By Throng Here," New Castle News (New Castle, PA), July 3, 1915.

"Large Crowd Hears Suffrage Speakers," The Franklin Evening News (Franklin, PA), July 23, 1915.

"Suffrage Campaign in Blair County Will Start on Sept. 17," The Altoona Times (Altoona, PA), September 16, 1915.

"Big Ovation in Town," Public Press (Northumberland, PA), September 24, 1915.

"Suffrage Meeting Tonight," Mount Carmel Item (Mount Carmel, PA), October 21, 1915.

"8,000 March in Philadelphia," The New York Times, October 23, 1915."

"Miss Louise Hall to Speak Here Tonight," Carlisle Evening Herald (Carlisle, PA), October 25, 1915.

"'Sandwichwomen' Seek Votes," Evening Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), October 28, 1915.

"Mrs. M.H. Bishop Is Honored by County W.C.T.U.," Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), September 26, 1917.

"Women Hear About Duties as Voters," Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), April 28, 1918.

"To Campaign for Loan and Suffrage," The Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT), September 22, 1918.

"Suffrage Wins Enough Votes To Pass Bill," The New-York Tribune, November 7, 1918.