Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890-1920

Biography of Elizabeth Askew, 1858-?

By Nancy Cole, retired librarian

Elizabeth Askew was born in 1858 in what was then Wheeling, Virginia. (The anti-slavery western part of the state seceded from Virginia after the beginning of the Civil War and Wheeling became the first capital of West Virginia.) She was the second of five children born to Thomas Evans Askew and Katherine Burris Askew.

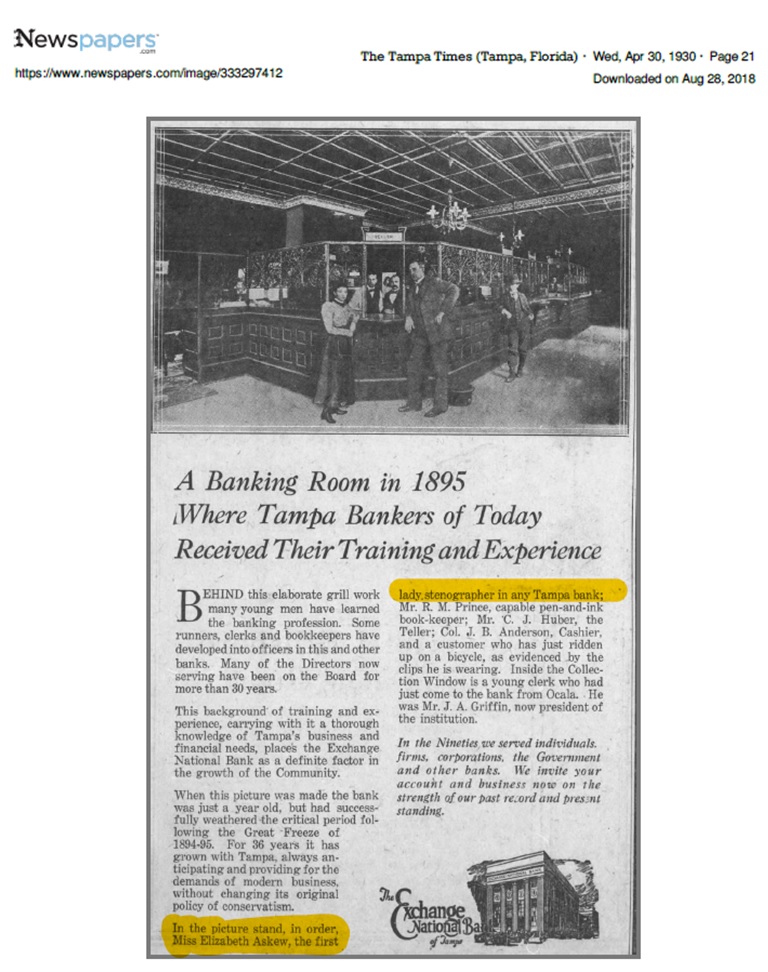

Some time later the family moved to Tampa, Florida. In 1894, when Askew was in her thirties, she became the first woman to be employed by any Tampa bank, as a stenographer according to an 1895 newspaper photo. In 1910 she remained single and continued to live in Hillsborough County, with her now 84-year old father, once again recorded as a stenographer.

Askew was a leader of two of the city's three women's clubs in the early 1900s. She was a founder of the Tampa Civic Association, which was a women's club, and was its secretary in May 1913 when the Tampa Times printed an article titled “Tampa Women Want to Vote.” Askew was quoted as saying that many women in Tampa representing groups as varied as her Civic Association to the United Daughters of the Confederacy signed the woman suffrage resolution presented to state legislators. Askew also noted in the story that a “clean-up law” recently passed in Kansas, at the initiative of women, showed what women can do when they have the vote.

The Woman's City Club was organized a few years after the Civic Association and focused its attention on the needs of working women and working-class families, including an employment bureau for women. Askew served two terms as its president, and declared the club's “crowning achievement” was a “hot lunch program for public schools at a minimum cost.”

In September 1913 Askew traveled to Chicago to learn about work there around civic and suffrage issues. The Chicago Examiner reported the Tampa Woman's City Club had introduced a bill to create a pension for mothers. Neither that bill nor the suffrage resolution had passed the state legislature, but the article noted Askew's optimism that by 1917 “public opinion will be so aroused that women will be given the vote.”

In November 1913 when the Florida Equal Suffrage Association was formed at a meeting in Orlando, Askew became its corresponding secretary.

None of the three Tampa women's clubs ever formally endorsed the vote for women.

The Tampa Tribune quoted extensively from a speech by Askew at the Civic Lunch Club in May 1914. “Opposition to the woman voter comes only from the ignorant and prejudiced, and the dishonest and vicious elements of political life. Men who earnestly desire to better conditions welcome the woman voter,” she said.

In December 1914 The Tampa Morning Tribune devoted nearly an entire page to “How Leading Tampa Women Regard Suffrage Movement” with essays from nine women including Askew. Opinions in the essays ranged from “Women's Place at Home” arguing that women should stay behind the scenes, to “For Woman's Liberation,” in which the writer marveled that some scientist “has not discovered the vast economic waste of the last twenty-five years of a woman's life” after her work of childrearing was finished.

A year later Askew was one of the Florida delegates to the convention of the December 1915 National American Woman Suffrage Association in Washington. D.C.

Still in Washington, Askew reported on the Women's Auxiliary of the Pan-American Scientific Congress in January 1916. “Recommendations were made of committees to promote Pan-Americanism solidarity of women of the Americas, and the study of the Spanish language in the United States and English in South America,” she wrote in a column for the Tampa Tribune.

Later in 1916 news articles indicated she relocated to Washington to work on the reelection of President Woodrow Wilson. When the national headquarters of the Women's Wilson Union opened in the U.S. capital, Askew was in charge of organizing its women's Democratic clubs across the country.

After Wilson's reelection, Askew represented Florida at his March 1917 inauguration, one of a group of 16 Democratic Party women representing 16 southern states. It was the first time that women were allowed to participate in a presidential inauguration parade.

Askew then returned to Florida where the Evening Star of Washington reported “she hopes to engage in legislative work for suffrage.”

Less than a month later in April 1917, she gave a “stirring address,” according to the Tampa Times, on women responding to the U.S. entry in World War I. “Back to the Farm” she told the Webster Woman's Club in Sumter County, Florida, “for the nonce is become the war cry in place of ‘Votes for Women.'” Yet she noted that “American women are hopeful that our government will accord to them the same generous recognition accorded by the revolutionists to the women of Russia. As the champions of world democracy, it can scarcely do less.”

After the January 10, 1918, vote in the U.S. House of Representatives approving the suffrage amendment (the first time), the Tampa Times ran an extensive on-the-scene report from Askew about the congressional discussion. She enthusiastically predicted congressional approval (which was not to come for nearly a year and a half). Then she wrote of “a most shameful moment” in the history of the Democratic Party. It was ”a most humiliating moment for the women of the south sitting in the gallery of the house of representatives on that memorable day, listening to the debate and noting that each southern representative who spoke in opposition to the measure, either of his own accord, stated, or was forced to admit, that behind his eloquence for state's rights was an unconquerable prejudice to the extension of any measure of suffrage to women now or at any time.”

By March 1919 Askew was back in Washington, D.C. and active in committees of the Political Study Club according to news accounts. There are no reports of her activity after that. There is enumeration for this Elizabeth Askew in DC or Florida in the 1920 or 1930 federal manuscript censuses.

Sources:

A banking room in 1895 where Tampa bankers of today received their training and experience. Tampa Times (Florida), 1930, April 30, p. 21.

A patriotic meeting of Sumter County club women. Tampa Times. (Florida), 1917, April 13, p. 8.

Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census. Wheeling Ward 3, Ohio, Virginia. Roll: M653_1368. Family History Library Film: 805369.

How leading Tampa women regard suffrage movement. Tampa Morning Tribune. (Florida), 1914, December 13, p. 64.

Interviewed in Chicago. Tampa Tribune (Florida), 1913, September 5, p. 9.

Miss Askew writes of Women's Congress. Tampa Tribune. (Florida), 1916, January 11, p. 10.

Organization of Florida Equal Suffrage Association completed. Ocala Evening Star. (Florida), 1913, November 11, p. 6.

Patriotic meeting of Sumter County club women. Tampa Times. (Florida), 1917, April 13, p. 8.

Suffragists make sweeping promises: Women speak before civic lunch club. Tampa Tribune. (Florida), 1914, May 22, p. 5.

Suffragists will win fight in Senate, Tampa woman says: Elizabeth Askew, who predicted success of the amendment in House, tells of dramatic moments – two congressmen left sick beds to vote for cause. Tampa Times. (Florida), 1918, January 23, p. 4.

Tampa woman represented Florida. Tampa Times. (Florida), 1917, March 5, p. 8.

Tampa women want to vote: Many of them signed resolution. Tampa Times. (Florida), 1913, May 8, p. 14.

Weatherford, Doris. (2004). Real women of Tampa and Hillsborough County from prehistory to the Millennium. Tampa, FL: University of Tampa Press.

Weatherford, Doris. (2015). They dared to dream: Florida women who shaped history. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

Women in politics. Pensacola Journal. (Florida), 1916, October 31, p. 5.

Women's Democratic Club formed in Washington. Pensacola Journal. (Florida), 1916, October 20, p. 5.