Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890-1920

Biography of Deborah Knox Livingston, 1874-1923

By Elisa Miller, Associate Professor of History, Rhode Island College, Providence, RI; Amanda Murphy, undergraduate student, Rhode Island College; and Delaina Toothman, graduate student, University of Maine, Orono, Maine

Member of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association; Member of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Party; Honorary Vice President of the Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association; President of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union of Rhode Island; Superintendent of Franchise (and Suffrage and Christian Citizenship) of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union; State Organizer, Legislative Chairman, and Campaign Director of the Maine Woman Suffrage Association; Vice President of the United League of Women Voters of Rhode Island

Deborah King Knox was born in Glasgow, Scotland on September 10, 1874 to James and Helen Reid Knox. She was reportedly a descendant of John Knox, a Scottish religious leader, on her paternal side. The family immigrated to the United States in 1884 when Knox was ten years old. They lived first in Lincoln, Rhode Island and then Pawtucket, Rhode Island, a city that was home to many immigrants and industrial factories and mills. Knox was active in community organizations at a young age, as early as age twelve in 1886. She participated in numerous church and Scottish organizations and the Women's Relief Corp, an auxiliary of the Grand Army of the Republic. She frequently gave readings at public events and meetings, developing strong skills in public speaking that she became noted for as an adult activist. In 1888, Knox gave a reading at a Sons of Temperance meeting, her earliest known activity in the temperance movement in which she later became a national and international leader. In 1892, she joined the Pawtucket Woman's Christian Temperance Union and graduated from the St. Xavier's Young Women's Academy in Providence. At some point after her graduation, Knox briefly taught school in Southern Rhode Island. In 1895, Knox participated in a one-year training school for missionary and social service offered by the New York Mission and Tract Society. She later gave lectures in Rhode Island about her experiences working in "the slums of New York."

After Knox returned from New York, she became heavily involved in community service and activism in Pawtucket and Providence. She became president of the Pawtucket Woman Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1896. She explained that she had met Frances Willard, national president of the WCTU, as a student (not clear if in Rhode Island or New York) and "was so impressed by the woman and the cause" that she became a temperance activist. She also was a member of the WCTU of Rhode Island and became its chair of Juvenile Work and State Organizer of the Loyal League in 1896. She attended the national WCTU convention in St. Louis in 1896 as well as many other years.

In addition to her temperance work, Knox participated in a wide variety of church organizations and activities. Through her church activism, she met Benjamin T. Livingston, whom she married on August 25, 1897. Livingston was a Pawtucket resident who also was a Scottish immigrant. Livingston was also a Christian activist and a graduate of Brown University. After their marriage, the couple moved to the Boston area for Benjamin to attend the Newton Theological Society to train to become a minister. While in Boston, Deborah Livingston served as secretary of the Boston WCTU. She also returned to Rhode Island on several occasions to give speeches at temperance organizations. At the end of 1899, the Livingstons moved to Providence, Rhode Island after Rev. Livingston was appointed the pastor at the Jefferson Street Baptist Church. In 1905, he later became pastor of the Union Baptist Church in Providence. The Livingstons' first child, a daughter named Helen Reid Livingston, after Deborah's mother, was born in 1899. Helen Livingston died at eighteen months in April 1902. Their second child, David K. Livingston, was born on December 2, 1907. In Rhode Island, Deborah Knox Livingston resumed her extensive community work, most notably in the WCTU of Rhode Island. She was elected president of the RIWCTU in 1904, a position that she maintained until late 1912 when she moved out of Rhode Island again.

Both nationally and in Rhode Island, the woman suffrage and temperance movements were closely related in goals, ideas, and membership. Livingston's earliest known activism on behalf of woman suffrage was a speech she gave in 1898 at the Rhode Island Young Woman's Christian Temperance Union in which she discussed the importance of suffrage to the temperance cause and that the national WCTU had established a suffrage department. In 1905, she became a member of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association (RIWSA), although she was a supporter of suffrage prior to becoming a member. She occasionally gave speeches on temperance at RIWSA meetings and RIWSA leaders gave speeches on suffrage at RIWCTU events. In the WCTU and the Y.W.C.A., Livingston regularly collaborated with leading Rhode Island suffragists including Elizabeth Upham Yates, Mrs. Carl Barus, Florence Garvin, and Jessie V. Budlong. Representing the WCTU of RI, she testified in favor of woman suffrage at a legislative hearing on a presidential suffrage bill at the Rhode Island State House in 1912. Speaking at a WCTU meeting in West Warwick in 1912, Livingston called for "the enfranchisement of women," which she believed offered "the only hope for the enforcement of the liquor traffic" as well as "other great social reforms now before the people of this country," including child labor, crime, disease, education, and prostitution. At a 1918 WCTU of Rhode Island event, Livingston praised the "the standing together of suffrage and prohibition now as the two greatest reforms before the country."

Most notably, in 1912, Livingston was appointed superintendent of franchise (it was later renamed the department of suffrage) for the national WCTU in 1912. She held the position until the ratification of the woman suffrage amendment in 1920. In this position, Livingston became a national leader in the suffrage movement, especially known for giving speeches on suffrage across the United States and internationally. She detailed her plan in "Department of Franchise," a pamphlet she wrote to guide WCTU members how to carry out her suffrage campaign. In the pamphlet, she detailed issues such as the color of the decorations needing to be yellow and white (the suffrage colors), the union requirements, the methods for the courses, and the press work. Livingston authored many other educational booklets handed out at WCTU gatherings, including "Woman Suffrage and Temperance," "Facts for Busy Women," and "Facts for Busy Men," She also wrote a song about suffrage and temperance called "The Advancing Host" that included the chorus:

Women want the vote, women want the vote,

To bring in prohibition, women want the vote.

Women want the vote, women want the vote,

To make a sober nation, women want the vote.

She attended the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1916 and delivered an invocation and speech. The Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association, which had previously been named the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Association, named Livingston an honorary vice president of the organization.

Livingston believed that suffrage would improve conditions for American society and women. She embraced maternalist ideas that women had special characteristics and need for the vote that they would use to make society more moral and better for women and children. She argued that women of all kinds of backgrounds wanted the vote in order to "right the wrongs, heal the wounds and bind up the broken-hearted" and that American government needed "some motherly enforcement." In a speech at the annual RIWSA convention in 1908, she proclaimed "the granting of the suffrage to women would make for the uplift of all womanhood and the protection of childhood; that it would result in laws which would help the temperance union to win in its war against the liquor traffic." As a result, she frequently stated that one of the most powerful enemies of woman suffrage was the liquor industry. She also saw woman suffrage as a religious opportunity and duty for Christians, explaining that in order to extend "the Kingdom of our Lord upon the earth, we urge you to demand the right and the power of the ballot, and to demand it NOW." Suffrage, for Livingston, and most temperance activists and other social reformers, was more about gaining a powerful tool for social change than about equal rights for women. She also tried to refute the idea that suffrage would hurt women's homes and femininity. At one speech she explained, "Men seem to think it will change the character of their homes. They seem to think their wives, daughters, sisters or mothers will lose something or acquire something." Livingston continued that, "In any suffrage State the women have lost none of their charm or efficiency [in the home]."

Deborah Knox Livingston had been giving readings at events and cultivating her public speaking skills since she was a child. In the 1910s, she emerged as a celebrated orator for suffrage and temperance in the United States and around the world. The Lewistown Journal in Maine declared that "her style of speaking was a revelation to all. A voice of singular sweetness, resonance and power; a diction that is direct and flowing; an argument that runs coherently throughout the address all indicated the source of her reputation as one of the most distinguished public speakers in the country." The article also noted that she was fair and rigorous in acknowledging and disproving arguments against suffrage. The Providence Journal reported that she "possessed a remarkable command of language, had a voice of compelling richness and was gifted with a powerful personality, all of which, combined, made her a valued public speaker."

In September 1912, Deborah Knox Livingston was re-elected to a ninth term as president of the WCTU of Rhode Island. A couple months later, she resigned the organization due to her moving to Bangor, Maine where Rev. Livingston had been appointed the pastor of the Columbia Street Baptist Church. In Maine, Livingston continued her suffrage and temperance activism. She was elected president of the Bangor YWCA in 1914 and was a founding member of the Bangor Suffrage Center. Bangor at this time was the gateway to points farther north and Livingston worked hard to make Bangor a center of suffrage activity for the area. The Suffrage Center held regular suffrage meetings designed to encourage respectable women to attend. She frequently testified about suffrage before the Maine state legislature. Livingston and her group brought before the Maine Legislature a proposed amendment that would provide women the right to vote. It looked, in 1915, as if that amendment were going to pass. Livingston argued before the Legislative Committee that boys and girls had equal educational opportunities, which lead to more women in industry, which in turn was affected by government. Women, therefore, should have a voice in government. Although the 1915 referendum bill passed in the Senate, it failed in the House. Livingston also continued to lecture about suffrage and prohibition across the country. In 1915 she gave a speech about woman suffrage to ministers at the West Virginia Methodist Episcopal Conference. The members passed a resolution in support of suffrage afterward at the convention. In 1916, the Maine Woman Suffrage Association appointed her its state organizer and legislative chairman.

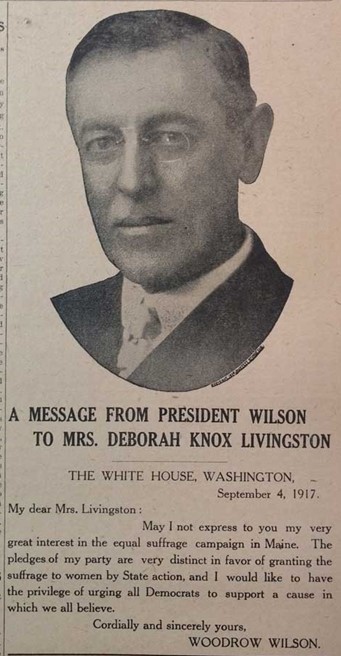

In 1917, the Maine legislature did approve a public referendum for woman suffrage in the state. When Governor Carl E. Milliken signed a resolution for the special election on February 23, 1917, leading Maine suffragists, including Deborah Knox Livingston, attended and were featured in a photograph of the event. The NAWSA organization provided the funds to hire Livingston to run a campaign in Maine to win support for the woman suffrage referendum. As part of this six-month campaign, Livingston traveled 20,000 miles across the state and gave 150 speeches on woman suffrage. President Woodrow Wilson sent her a letter in support of the Maine suffrage campaign, that several newspapers covered on their front pages. The letter said:

My dear Mrs. Livingston:

May I not express you my very great interest in the equal suffrage campaign in Maine. The pledges of my party are very distinct in favor of granting the suffrage to women by State action, and I would like to have the privilege of urging all Democrats to support a cause in which we all believe."

Cordially and sincerely yours,

Woodrow Wilson

The suffrage newspaper, The Woman's Journal, praised Livingston's work in Maine as "making many converts to cause by earnest work." The article claimed that "practically every man who hears her message" remarked "'I shall vote for the referendum.'" Under Livingston's direction, the article stated, 65 Maine cities and towns formed suffrage campaign committees. An article about a speech she gave at the Lewiston Chamber of Commerce in Maine demonstrates how she tried to win over male opponents of suffrage. When a businessman in the audience objected that women did not know enough about business to vote, Livingston asked him if he knew of any of the tariff rates other than the ones concerning his own business. He answered no. She then instructed him to ask his wife if she knew. The man came back shortly afterward with the response of "Tariff!!! You won, she did know." "Of course she knew," said Mrs. Livingston. "She understood her business in life."

During the 1917 campaign, Livingston became involved in a feud with Maine suffragist Florence Brooks Whitehouse over the types of tactics the women should use in getting the referendum passed. Livingston openly objected to the "picketing" of the White House by the militant suffragists of the Congressional Union and the National Woman's Party and issued a statement against these tactics. The Providence Journal reported that Livingston's statement claimed that "the Maine suffragists will go on in their peaceful methods of appealing to voters for their support in securing for the people of Maine full enfranchisement next September." Earlier, in 1913, Livingston refused to take a stand against the militant tactics of suffragettes in England, saying that "We are not here to commend or condemn [them]."

Maine voters failed to pass the suffrage referendum in September 1917. Following the defeat, Livingston wrote a report about the campaign explaining "Maine presented as difficult a field for the conducting of a suffrage campaign as has ever been faced by any group of suffragists in any part of the country." The Courier-Gazette quoted her saying at a Maine WCTU meeting that the 1917 campaign was "merely the first round of a battle which could end in but one way—the establishment of the political equality of womanhood." She urged the members to "go home and teach their men three things: First, that women do vote; second, they want to vote, and third, that they will vote!" At the end of 1917, the Livingstons moved back to Rhode Island where Rev. Livingston had been hired as superintendent of missions for the Rhode Island Baptist State Convention.

During World War I, Livingston became active in the war effort. NAWSA leaders and Livingston believed that war voluntarism could help the woman suffrage cause by demonstrating women's patriotism. The Woman's Journal quoted Livingston as explaining that, "The suffragists of the State are as patriotic as any group of women in Maine, perhaps more so, for they have been a long time in seeking to share the burden of government, and they can be counted on to bear their share in the great situation which has been created by the fact that we are in war." She claimed that in the long run, the war "will not be a hindrance [to suffrage], but a tremendous help." In 1918, YWCA leaders appointed Livingston to their National War Council. As part of her service for the YWCA, she made a speaking tour of the United States in a campaign to raise $170,500,000 for the war effort. She visited factories where women were doing industrial work creating war supplies. At a speech she gave at Gorham Manufacturing, a munitions factory in Phillipsdale, Rhode Island, she told the women workers there that "the success of the allied nations depended largely upon their efforts." To a male audience, she stated, "It has been said that women cannot bear arms but they have borne the armies of the world. Today woman stands at the bench making arms that may be placed in the hands of her son." In this way, Livingston hoped to use women's war work to gain support for suffrage.

In the article, "Why Maine Women Need the Suffrage" in The Women Citizen suffrage journal, Livingston wrote about the problems women would face at the end of the war. She argued women should have a voice because important issues such as women in industry, care for dependents, public health, and food affected women more than men. In a speech on "Americanization," she emphasized the important roles that foreign-born women played during the American war effort, at home and in industry. The WCTU of Rhode Island later referred to Livingston as "patriotism incarnate" during the war. She gave numerous speeches about women's industrial work during the war.

When the Livingstons returned to Providence at the end of 1917, she continued her local and national suffrage and temperance work. In December 1917, she traveled to Washington, D.C. with other local suffrage leaders to lobby Rhode Island senators and congressmen about the woman suffrage constitutional amendment. She gave a speech to the politicians; afterward, Senator LeBaron B. Colt said, "I do not think I ever heard the question presented with such dignity, eloquence and convincing force." Livingston became a member of the Rhode Island Woman Suffrage Party (RIWSP), a local suffrage organization that was affiliated with NAWSA. In 1919, she served as a RIWSP delegate to the NAWSA convention in St. Louis. As the woman suffrage amendment grew more likely in 1919, she joined a local branch of the League of Women Voters, an organization that developed out of NAWSA. Leading suffragists and league chairmen met with the Rhode Island Governor, R. Livingston Beeckman, in 1919 to lobby for a special legislative session for Rhode Island to ratify the suffrage amendment. Livingston attended the meeting and gave a speech in which she "urged that the [Rhode Island] General Assembly be called immediately lest Rhode Island fall among the very last of the States to ratify the constitutional amendment." She also attended "Women's Independence Day" events on July, 1, 1919 to celebrate the first day that women in Rhode Island could register to vote in the 1920 presidential election. (Rhode Island had passed a presidential suffrage bill in 1917.)

After the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, Livingston became a leader in the Rhode Island League of Women Voters organization. She was a founding member in 1920 of the United League of Women Voters in Rhode Island, an organization that consolidated different Rhode Island leagues, and was elected its 2nd vice president and a member of its executive committee. She represented the Rhode Island League at the national League of Women Voters convention in 1921. In 1921, she also chaired its committee on citizenship as well as served as national WCTU's director of Christian Citizenship (the new name for its department of franchise and suffrage following the Nineteenth Amendment.) As director of citizenship for the WCTU, she emphasized the importance of civic education for women, Americanization for foreign-born women, and using the vote to enforce prohibition and other Christian goals. She published Studies in Government, a manual that was used in WCTU citizenship courses and serialized in its journal, The Union Signal. She continued her lecture tours across the country. In 1921, at the Kentucky state WCTU convention, Livingston gave a speech about women's duties as new voters. The Union Signal reported that she "held the audience spellbound as she graphically unfolded to us our privilege and opportunity as newly enfranchised Christian citizens, to help elect better officials who will enforce the law, and to vote for all that makes for happier homes and better civic conditions."

In 1922, the Livingstons moved to Newton, Massachusetts when Rev. Livingston was hired as the general secretary of the Evangelical Alliance of New England. Deborah Knox Livingston maintained a very hectic schedule traveling and lecturing nationally and internationally in 1922 and 1923, including a six-month speaking tour on temperance in South Africa as a representative of the World's WCTU. South African government leaders had invited her to come the country to promote temperance among European residents of the country. In the summer of 1923, she fell ill, suffering from exhaustion and a reported "nervous breakdown." On August 5, 1923, she died at the age of forty-nine at her summer home in Osterville, Massachusetts on Cape Cod. She was buried in the Hillside Cemetery in Osterville and her gravestone was engraved with the statement, "A Soul Aflame for Christ and Righteousness. World Wide She Served." When she died, Livingston was the chair of the committee planning the WCTU's 50th anniversary celebrations for 1924. She did not live to celebrate that anniversary but did witness the achievement of the Eighteenth Amendment for prohibition and the Nineteenth Amendment for woman suffrage, causes to which she had devoted twenty years of her short life.

Livingston's early death shocked those in her local, national, and international activist circles. Obituaries for her appeared in newspapers across the country. The Providence Journal stated that she was an "internationally famous feminist" who worked tirelessly for "the cause of woman's world-wide enfranchisement." The WCTU of Rhode Island held a memorial service for her in 1923 that was attended by members and officials of the many local organizations in which Livingston had participated, including the Church Federation, the Young Women's Christian Association, the Missionary Societies, the Federation of Women's Clubs, the Consumer's League, the League of Women Voters, the Suffrage Association, the Anti-Saloon League, the Dexter Street Mission, and the Federation of Women's Church Societies. The RIWCTU established the Deborah Knox Livingston Memorial Fund to help advance the causes of civic education and prohibition and unveiled a portrait of her.

The RIWCTU also published a memorial booklet about Livingston that included tributes to her from individuals and organizations across the world. The United League of Women Voters of Rhode Island wrote that organization had lost "one of its most valued and distinguished members," whose services and advice were critical during its formation. It continued, that Livingston "unreservedly stood for the advancement of causes for human betterment" and that "The League, grateful for her life and for her active interest in its work, deeply mourns her loss." Anna Adams Gordon, president of the international and national W.C.T.U. stated, "Our World's and National Woman's Christian Temperance Union have suffered an irreparable loss through the passing of our beloved leader of the Christian Citizenship Department." A Johannesburg newspaper reported, "Her reputation was worldwide, for she had spoken in the British Isles, in Canada and in many countries of Europe, as well as in her own land, where she was an acknowledged leader among women." The WCTU journal, The Union Signal explained that, "She held before us the hope of a day when every woman in her place in the home, the office, the school, the factory should come to recognize in the ballot her opportunity to serve her family, her community, her nation and the world."

Local organizations continued to mourn the loss of Deborah Knox Livingston for many years. During the WCTU of Rhode Island's celebrations for the WCTU's 50th anniversary in 1924, they held a memorial meeting for Deborah Knox Livingston. The following year, the organization held a Deborah Knox Livingston tribute pageant at its annual convention. The WCTU of Rhode Island planted a tree in her honor at the Roger Williams Park in Providence in 1928. In 1930, the Rhode Island League of Women Voters included Livingston on its memorial honor roll in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the suffrage amendment. Members of a local branch of the WCTU in Rhode Island renamed the organization the "Livingston Union" and celebrated her birthday at an event in 1963.

Sources:

Ida Husted Harper, ed. The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 6: 1900-1920 (New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company, 1922), chapter 18 (Maine). [LINK]

Ida Husted Harper, ed. The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 6: 1900-1920 (New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company, 1922), chapter 38 (Rhode Island). [LINK]

Rhode Island Equal Suffrage Association Records, 1868-1930, Rhode Island State Archives, Providence, RI.

Records of the League of Women Voters of Rhode Island, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Rhode Island.

Ancestry.com: United States censuses, Rhode Island censuses, Scottish census.

"Deborah King Knox Livingston," Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/41853193/deborah-king-livingston.

"Helen Reid Knox," Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/220503963/helen-knox.

Sara M. Algeo, The Story of a Sub-Pioneer (Providence, RI: Snow & Farnham Co., 1925).

Deborah Knox Livingston, Studies in Government (Evanston, IL: National Woman's Christian Temperance Union, 1921).

Deborah Knox Livingston, Woman Suffrage and Temperance (n.d) in National American Woman Suffrage Association Records: General Correspondence, -1961; Livingston, Deborah K. - 1961, 1839. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss3413200689/.

Deborah Knox Livingston, "The Real Opponent of Woman's Suffrage" (n.d). League of Women Voters Mrs Wing's Scrapbook 69.129.2. 79, https://digitalmaine.com/lwvme/79.

Elizabeth Putnam Gordon, Women Torchbearers: The Story of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (Evanston, IL: National Woman's Christian Temperance Union, 1924).

"Maine Suffrage Who's Who," Maine State Museum, https://mainestatemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Maine-Suffrage-Whos-Who.pdf.

Shannon M. Risk, "'In Order to Establish Justice': The Nineteenth-Century Woman Suffrage Movements of Maine and New Brunswick," (Ph.D. diss, Univ. of Maine, 2009).

Paul D. Sanders, ed., Lyrics and Borrowed Tunes of the American Temperance Movement (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 91-92.

"Suffragists in Maine," Turning Point Suffrage Memorial, https://suffragistmemorial.org/suffragists-in-maine/

Women's Christian Temperance Union of Rhode Island, Memorial: Deborah Knox Livingston (1923).

"Women's Long Road: 100 Years to the Vote," Maine State Museum, https://mainestatemuseum.org/exhibit/suffrage/referendum/.

"Maine Suffrage Who's Who," Maine State Museum, https://mainestatemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Maine-Suffrage-Whos-Who.pdf

"A Message from President Wilson to Mrs. Deborah Knox Livingston," The Brunswick Record, September 7, 1917. From "Women's Long Road: 100 Years to the Vote," Maine State Museum, https://mainestatemuseum.org/exhibit/suffrage/they-persisted/.

Anna B. Wheeler, "Kentucky State Convention: Educational, Brilliant, Enthusiastic," The Union Signal 48, No. 50 (December 29, 1921), 13.

"Ballot Urged for Use in Liquor Traffic Fight," The Providence Journal, October 31, 1913.

"Campaign in Maine Opens," The Woman's Journal 48, No. 13 (March 31, 1917), 75.

"Committee Vote Yes in Maine," The Woman's Journal 44, No. 8 (February 22, 1913), 1.

"Deborah K. Livingston Is Against Militancy," The Providence Journal, July 6, 1917.

"Deborah Knox Livingston," The Providence Journal, November 9, 1918.

"Deborah Livingston," The Providence Journal, November 9, 1918.

"Defiance of Law Stirs 'Dry' Leader," The Providence Journal, October 9, 1919.

"Dry Enforcement Programme Urged," The Providence Journal, January 7, 1922.

Emily Burnham, "Maine Was an Early Battleground to Secure Women's Right to Vote, Bangor Daily News, August 17, 2020.

"Full Course Students," New York City Mission Monthly (June 1907), 19.

"Governor Unmoved by Women's Pleas," The Providence Journal, September 30, 1919.

"Livingston," The Providence Journal, April 23, 1902.

"Livingstone-Knox Nuptials," The Providence Journal, August 26, 1897.

"Livingston Union," The Providence Journal, September 9, 1963.

"Mothers' Club Hears Problems Discussed," The Providence Journal, May 10, 1910.

"Mrs. Deborah Knox Livingston," The Providence Journal, October 4, 1907.

"Mrs. Deborah Knox Livingston Addresses W.C.T.U. Here," The Providence Journal, October 4, 1919.

"Mrs. Deborah Knox Livingston, Widely Known Temperance Worker, Dies in Osterville, Mass.," The Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vermont), August 6, 1923.

"Mrs. D.K. Livingston," The Providence Journal, August 6, 1923.

"Mrs. Livingston at Literary Union," Lewiston Evening Journal (Lewiston, Maine), November 5, 1919.

"Mrs. Livingston Gives Opinions," The Woman's Journal 48, No. 16 (April 21, 1917), 75.

"Mrs. Livingston on the Suffrage Cause," The Lewiston Daily Sun (Lewiston, Maine), June 19, 1917.

"Music and Speaking Mark Tree Planting," The Providence Journal, May 13, 1928.

"Noted Apostle of Prohibition Dies," The Boston Globe, August 6, 1923.

"Noted Temperance Advocate is Dead," The Providence Journal, August 6, 1923.

"Plan Safeguarding Young Women," The Providence Journal, May 23, 1911.

"President Wilson Urges All Democrats of Maine to Vote 'Yes,'" The Bangor Daily News (Bangor, Maine), September 7, 1917.

"Resolutions Voted for Rev. B.T. Livingston," The Bangor Daily News (Bangor, Maine), November 5, 1917.

"Rhode Island," The Woman Citizen 4, No. 20 (December 6, 1919), 531.

"R.I.W.C.T.U.," The Providence Journal, January 12, 1897.

"R.I. Women Voters Give Jubilee Feast," The Providence Journal, July 2, 1919.

"State Suffragists Ask for Congressmen's Support," The Providence Journal, December 12, 1917.

"Suffrage and Prohibition Discussed by W.C.T.U.," The Providence Journal, January 19, 1918.

"Suffrage and Prohibition Lauded at W.C.T.U. Banquet," The Providence Journal, January 20, 1917.

"Suffrage in the State of Maine," The Woman's Journal 48, No. 20 (May 19, 1917), 117.

"Suffrage Strong at Dry Conclave," The Woman's Journal 47, No. 48 (November 25, 1916), 379.

"Temperance and Home Missions," The Providence Journal, April 12, 1906.

"The Liquor Traffic," The Providence Journal, February 4, 1897.

"The WCTU," Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, Australia), September 24, 1923.

"Total Abstinence," The Providence Journal, November 12, 1898.

Wayne E. Reilly, "Bangor Club Women Battled for Rights a Century Ago," Bangor Daily News (Bangor, Maine), June 7, 2015.

"W.C.T.U. Considers Regional Reports," The Providence Journal, February 5, 1921.

"W.C.T.U. Convention," The Providence Journal, October 7, 1896.

"W.C.T.U. of State Amends Organic Law," The Providence Journal, October 4, 1907.

"W.C.T.U. Praises R.I. State Police," The Providence Journal, October 23, 1925.

"W.C.T.U. Season Here is Opened," The Providence Journal, October 4, 1919.

"W.C.T.U. Speaker Hopes for Victory," The Providence Journal, May 16, 1914.

"West Virginia," The Woman's Journal 46, No. 41 (October 9, 1915), 323.

"The White Ribboners," The Courier-Gazette (Rockland, Maine), September 25, 1917.

"Woman Suffrage Bill Discussed," The Providence Journal, April 18, 1912.

"Women's Clubs," The Providence Journal, September 21, 1924.

"Women Continue to Struggle for Vote," The Providence Journal, October 2, 1908.

"Women Urged to Enroll for Work at Phillipsdale," The Providence Journal, October 29, 1918.

"Women Voters' League Announces Election Result," The Providence Journal, October 10, 1920.

"World Prohibition is Declared Only Solution of Enforcement," The Providence Journal, October 24, 1922.