What Factors Led to the Success of the Historic 1970 Sex Discrimination Complaint

Filed against the University of Michigan?

Filed against the University of Michigan?

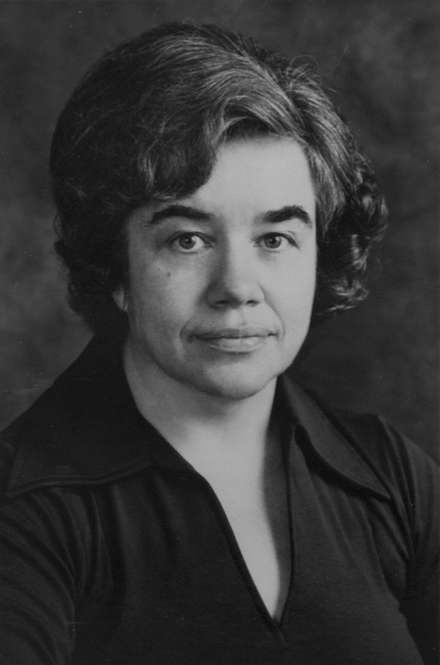

Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library, Jean King Papers, Box 7, Photographs Folder, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Documents selected and interpreted by

Sara Fitzgerald

September 2013

Beginning in 1970, a handful of women, centered in Ann Arbor, Michigan, found a way to unleash the power of one American institution—the federal government—against another powerful institution—the University of Michigan. And within a matter of years, the group of faculty, staff members, students and local residents helped spark a revolution in academic hiring practices that would reverberate all across the country.

The complaint filed against Michigan by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) was the first that led to the withholding of federal contracts until the University took specific actions to address findings that it was guilty of sex discrimination. Among hundreds of complaints filed against universities all across the country during this period, the women at Michigan achieved the most direct success.

The outcome there can be traced to a number of key factors:

- the dogged, political leadership of a few women who had witnessed (and experienced) the discriminatory practices but were now beyond the reach of the system they were challenging;

- a few sympathetic "white knight" federal civil servants, in Washington and Chicago, who helped the women identify a course of action and continued to support their challenge;

- a local environment in which women were rapidly building informal support networks around a range of new concerns;

- the climate on a campus that had recently addressed similar issues regarding minorities; and

- the initial response of the university's top male administrators who, in most cases, failed to acknowledge that the women's issues were as valid as those that had recently been addressed for minorities.

Ironically, the prominence of those male leaders and their own strong institutional networks helped ensure that the University of Michigan's response would become the template for addressing the issues at college campuses all across the nation.

The episode demonstrates the ultimate effectiveness of what one of the women involved described as "the three-legged stool": a government agency that gave credence to the women's complaints of discrimination, a moderate group that could implement social change, and what she described as "the mob in the courtyard" demanding change. "Whatever they're yelling," she concluded, "tends to make whatever the bureaucrats and the middle are saying look very reasonable."[1]

While HEW could have limited its investigation of the University of Michigan, as a large public research university, to a regular contract compliance review, the women on campus were uniquely successful in bringing issues to the attention of HEW staff, keeping the investigation on track, lobbying members of Congress for support, engaging friendly media outlets, and spreading the word about their experience nationwide.

The years that provide the focus of this study cover a period during which affirmative action began to be viewed as a remedy for past discrimination, particularly for minorities. As at many times in U.S. history, the plight of women was viewed through a different lens than the one that was applied to African Americans—and that was the case at the University of Michigan in the early 1970s. Further, the episode helped set the stage for the passage of what became known as "Title IX" of the Education Act Amendments of 1972, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex in educational institutions that received federal funding.

The groundwork was first laid in October 1963, when the President's Commission on the Status of Women released the results of nearly two years of study on factors impacting the lives of American women. One section highlighted the educational challenges faced by American women, particularly those who wished to return to college after their children were born. Another focused on recommendations regarding employment policies and practices "under federal contracts" (see Document 1).

But as the years went by, and new anti-discrimination laws were passed, women in American academia were frustrated by the fact that they remained unprotected. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited many forms of discrimination, but Title VI, which barred discrimination in federally assisted programs, did not mention sex discrimination. Title VII, which barred most forms of job discrimination on the basis of sex, included an exception for administrative and professional positions. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 included a similar provision, effectively excluding women faculty members from the law's protections.

But on October 13, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11375, amending an earlier executive order to prohibit sex discrimination in the federal workplace. A second part of the executive order, which would take effect a year later, also prohibited sex discrimination by federal contractors (see Document 2). News coverage at the time focused more on the potential impact on women in the federal workplace,[2] and government compliance activities had generally been focused on federal construction contractors and their record of hiring minorities. In addition, the Labor Department was slow to issue regulations and guidelines to enforce the new provisions. Whatever the reason, it would be another two years before academic women fully recognized the new tool they had been given.

One of those women was Dr. Bernice Sandler, who had been frustrated in her attempts to win an academic appointment at the University of Maryland. Sandler, who held a doctorate in educational psychology, had been teaching part-time when she asked a fellow faculty member why she had not been considered for one of the department's seven openings. "Let's face it," he replied, "You come on too strong for a woman." Shortly after that, Sandler was also rejected by a research executive who explained he couldn't hire a woman because she would want to stay home when her children were sick. Finally, an employment agency reviewed Sandler's résumé and pronounced that she was "not really a professional" but "just a housewife who went back to school" (see Documents 3 and 4).

That same year, Sandler became affiliated with the Women's Equity Action League (WEAL), which she viewed at the time as a "middle-of-the-road" group, focused mostly on issues related to legal and tax inequities, education and employment. "I would never have joined NOW [the National Organization for Women]," she recalled, "because it picketed and looked 'very radical' to someone like myself who was just discovering that perhaps there was indeed discrimination" (see Document 3).

Sandler began researching potential remedies for sex discrimination in academia and had what she recalled as a "Eureka experience" when she read a study by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and found a reference to Executive Order 11375 in a footnote. Sandler phoned the Labor Department's Office of Federal Contract Compliance, and found a supportive civil servant in Vincent Macaluso. Macaluso told her he had been hoping to find someone who would be willing to pursue a complaint, and coached Sandler on how to do it.[3] Macaluso, she recalled, "told me that because it is not a lawsuit, it is an administrative charge, and he said, 'You don't need a lot of information. You can just use a little bit of information and it is a valid charge.' He said, 'We don't even have a form.' "[4] He told her to count the number of women in each department at the University of Maryland, which she did by using a staff directory and visiting departments where the names were ambiguous.[5]

The first complaint, filed on January 31, 1970 against the University of Maryland and all universities with a pattern of discrimination, was signed by Nancy Dowding, president of WEAL. Macaluso told Sandler "you need a title,"[6] so she began identifying herself as chairman of WEAL's Action Committee on Federal Contract Compliance and went on to file more than 250 complaints against individual universities (see Documents 3 and 4). But among all of those complaints, the attention of HEW became focused first on the one filed against the University of Michigan. A major reason why was the fact that one of its signatories was a skilled and determined local attorney named Jean L. King.

King had earned bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Michigan and then worked in a variety of clerical jobs at the university before giving birth to three children. She became active in the Democratic Party and attended the party's 1964 national convention. At the convention, she recalled, she overheard a local lawyer, Peter Darrow, make a joke about Millie Jeffery, a leader in the United Auto Workers union. King decided that she would never be taken seriously as a woman unless she earned a law degree.[7]

King was admitted to the University of Michigan Law School in 1965 at the age of 41, at a time when there were no female professors and only nine other female classmates. She made the editorial staff of the Michigan Law Review during each of her three years, and upon graduation in 1968, the American Trial Lawyers Association recognized her as the outstanding graduate in her class for her "scholarship and academic achievement, responsible leadership in student affairs, and demonstrated concern for the problems of American society."[8]

Through her secretarial jobs and her party work, King had experienced the same kind of sex discrimination that other female employees and students at the University had endured. She also had gained an understanding of the politics of the University:

Maybe the hardest thing to understand about 1970 was the lack of contact between women at the university—staff as well as professors. So they couldn't share with each other what was happening to them. They just sort of individually got angry. It wasn't a movement at all. I was more aware of this because I had been secretary of a department, so I had observed our one woman professor, so I could see what she was going through. And Ted [Thedore M. Newcomb, professor of social psychology] had contacts all over the university, mostly with men, not with women. I worked all over the university. . . . I knew the university pretty well. And I knew the hiring system, so I came to this with a lot of experience. Because the guy I was working with was important, I kind of absorbed what he knew.[9]

Early in 1970, King organized a group of local friends to support FOCUS on Equal Employment for Women, a coalition of women's groups who opposed President Richard M. Nixon's nomination of U.S. Circuit Judge G. Harrold Carswell to the U.S. Supreme Court.[10] King recalled later that "10 people were enough" to form any organization, and that her own FOCUS group may have, in fact, only met in person on one occasion, "sitting on my piano bench."[11]

At a meeting in New York in the spring of 1970, King heard Bernice Sandler outline how WEAL was using the federal executive order to challenge sex discrimination at universities. At the time, King felt that she did not have the time to pursue a complaint because she was working for the Michigan Crime Commission, studying for the bar exam, building up the new Women's Caucus of the Michigan Democratic Party and raising three children. Instead she approached Jean Campbell, director of the university's Center for the Continuing Education for Women, but Campbell did not follow through. "At the time," King recalled in 1999, "I didn't realize the importance of an inside/outside strategy. People inside can't afford to complain or actively pursue complaints—at least they couldn't at that time, and frequently even now—or they will lose their jobs." (See Document 8) "Jean Campbell," she noted later, "wouldn't have lasted five minutes."[12]

But later that spring, King decided to approach the members of FOCUS about pursuing a complaint. The group included a few Ann Arbor residents, University faculty members and staff, and at least one graduate student. In March, an article in the local Ann Arbor News said the group included "about 20 to 40 women"—probably an exaggeration—and that it was "working to eliminate bias toward the working woman and anything discriminating against her ability to earn a living."

The article featured a woman named Mary Dabbs, who was, it said, "married with children" like most FOCUS members. Dabbs, it added, "is not a radical feminist who believes that women have been oppressed by men, yet she is sympathetic toward some who are radical." Group members were described as working on a range of issues, including housing and credit discrimination and the need for better child care.[13]

Psychology Professor Elizabeth "Libby" Douvan was one of the few professors who was involved with FOCUS, and eventually helped prepare the group's statistical analysis of the status of campus women. (Douvan may, in fact, have been the female faculty member that King got to know when she worked as a secretary in the psychology department.) Douvan recalled that King "just called a few old friends and said, 'Would you come by my house on Saturday?' . . . We were mainly going to talk about the fact that the women on the faculty were not paid what the men were, and didn't get the same kinds of opportunities."[14]

The spring of 1970 was a time of crisis for the University of Michigan. Starting in late 1965, the University, as a federal contractor, had been prohibited from engaging in job discrimination against minorities. A year later, a contract compliance team had visited the University and in March 1968, University officials were still wrestling with how to address the paucity of minorities in the professorial and graduate student ranks. "It seems clear to me," the dean of the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, the University's largest academic unit, wrote his superior at that time, "that only affirmative action, definitely focussed [sic], toward recruitment of Negro graduate students or professors will produce some results." (See Document 5) But little progress was made over the next few years, and in March 1970, a number of student groups organized as the Black Action Movement (BAM) called for a campus-wide strike to promote the admission of more minorities. After eight days, and the cancellation of classes by hundreds of professors and teaching fellows, the University's Regents committed the institution to working toward achieving a 10 percent African-American enrollment by 1973.

King later recalled that she would not have considered filing a complaint "had there not been a BAM movement 2-3 months ahead." She had learned her lessons through her work with the Democratic Party. "I don't want the university to be able to play blacks against women. . . . Because that's the usual response, at least it was at that time. Women ask for something and they say, 'Oh, well, you don't want black people to have it?' So strategically it was better to wait."[15]

At the same time, Kathleen Shortridge was working on a master's degree in journalism and researching the status of women on campus for a seminar on investigative reporting. Two weeks after the end of the BAM strike, The Michigan Daily, the student newspaper, published the results of her research in a story with the provocative headline "Women as University Nigger; Or How a Young Female Student Sought Sexual Justice at the 'U' and Couldn't Find It." (see Document 6) Shortridge said that when King "learned that I was pulling together data that could be the basis of the complaint, she contacted me about it."[16] Shortridge also served as the initial press contact for FOCUS.

Joining King in signing the FOCUS complaint was Mary Yourd, a Republican who was married to an administrator in the Law School. Douvan recalled that it "was decided that that would be better for them to bring the suit, challenge the University because the women on the faculty might get some kickback from taking part in that." (see Document 9) Douvan noted that Yourd was "the most charming, warm, loving--and angry woman. I mean, she was pissed off!" She also recalled King's "generosity of spirit," telling those with University connections: "Well look, you guys are vulnerable, we're not. We'll take the fall."[17]

On May 27, 1970, FOCUS filed its complaint. (see Document 7) In their letter, King and Yourd called on the U.S. Labor Department to insist that all federal agencies doing business with the University of Michigan enforce the executive order barring discrimination on the basis of sex. It made a number of specific complaints about the university's hiring and admissions policies:

- The University enforced quotas in its admissions practices that discriminated against women—only 45 percent of entering freshmen were women, even though their grades and test scores were higher than those of their male counterparts;

- Although women held 11 percent of the doctorates awarded in the past decade, only 6.6 percent of the University's professors were women;

- The disparity in hiring was worse in schools such as the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, where only 34 of the 900 professors were women.

- Women in clerical positions were expected to do administrative and supervisory work without receiving pay commensurate with their duties.

King and Yourd concluded by saying, "The investigator should contact us for the names of persons who will testify in support of this complaint."

More than 40 years later, Sandler reflected on the reasons why the Michigan women were more successful than women who had filed complaints against other institutions. King, she recalled, had recognized the ramifications of the executive order more quickly than many other women in academia because she had been trained as a lawyer. "She saw the big picture immediately." Because of King's legal experience, Sandler added, the Michigan data were gathered and prepared more carefully than in many of the other complaints.

Because King and Yourd did not work for the university, they also did not face potential retribution from their employer. Sandler recalled that at most of the universities where complaints were filed, "people weren't outside" of the system.

Finally, she said, Michigan was unusual in that many of the women who supported the complaint were highly placed. They weren't, she said, "the man-hating stereotype." It gave the complaint "much more credibility" and "made a huge difference in how things went internally." They also had women involved "who weren't employed by the university but were married to the university. Their husbands were secure in their jobs. It made a huge difference."[18]

King carefully followed two strategies out of the playbook that Macaluso had outlined for Sandler. She made skillful use of the media, particularly sympathetic women reporters who were encountering sex discrimination themselves in their workplaces. Sandler advised sending a copy of the complaints to the local newspapers, rather than to the universities. "The plan was," she said, "why give the university time to respond publicly; this way they would get a call from the newspaper saying, 'Charges have just been filed against you in terms of sex discrimination." They wouldn't know what to do because they hadn't seen it. Sometimes they would say things they shouldn't."[19] When the Michigan complaint was filed, copies were sent to reporters in Detroit and Ann Arbor with a press release that Shortridge had prepared.

In its initial response to the complaint, a University spokesman said, "We shall try to do better." Any discrepancy in the status enjoyed by men and women on campus, he said, reflected a "general situation" in society. He observed that the University of Michigan was ahead of many colleges in that it did have a female member of the Board of Regents, a female dean (of the School of Nursing) and a female vice president (albeit one who was a close associate of the president and was serving on an acting basis.)[20] The response demonstrated the initial view of the University's top administrators that the complaint was a nuisance and that sex discrimination was not a problem that needed to be taken seriously.

Macaluso had also stressed to Sandler the importance of following up with letters to members of Congress, getting them to ask federal officials about the status of the complaint as it moved through the departmental bureaucracy. King said she believed that the reason the Michigan complaint was ultimately successful was because of the extent of follow-up lobbying that she and Yourd had done. Over the course of the first summer, they wrote more than 80 letters to members of the Michigan congressional delegation, both Democrats and Republicans, sending a new one every time there was turnover at the top of the Labor Department or HEW.

King recalled, "We gradually began to sense that there were a lot of women in Congressional staff jobs (mostly low level, none administrative assistants, mostly anonymous) that were rooting for us. Some of them able to sign their bosses' names. They could at least sometimes put our letters on top of their bosses' piles of mail." (see Document 8)

The Labor Department had decided that HEW would be the lead agency to review complaints filed against universities.[21] In June, HEW issued a memorandum to field personnel, requiring them to include sex discrimination in their contract compliance investigations, whether or not a complaint had been filed.[22] In August, just over two months after King and Yourd's complaint was submitted, HEW sent an investigative team to Michigan—"really the speed of light in federal investigations," King recalled.[23]

HEW had previously begun to investigate a complaint filed against Harvard University, but there the investigation had focused instead on racial discrimination.[24] The same thing might have happened at Michigan, because Clifford Minton, the head of the investigative team from HEW's Chicago regional Office of Civil Rights, turned out to be experienced with discrimination on the factory floor, and, in King's words, did not seem to understand the "grapevine system of hiring faculty at a university." (Document 8) At the end of his team's visit, he told a reporter that the investigators had received "only general allegations" and that no individual had stepped forward to complain about sex discrimination.[25]

(Later that fall, William J. Cash, an assistant to University President Robben W. Fleming and the University's highest-ranking African-American administrator, observed that "HEW was coming anyway; they came to see both [potential discrimination against minorities and women]. HEW actually came to review minority groups, but they also had this complaint from FOCUS and decided to investigate it. Just before they arrived we got a complaint from FOCUS. They come every six months to do a checkout on-site visit. . . . Michigan happened to be the target institution in the Midwest.") (see Document 26)

King, however, was not to be deterred, and complained to Minton's supervisor, John Hodgdon, the director of the Chicago regional office (and "a real mensch," she recalled).[26] Hodgdon was sympathetic, and a new investigator was assigned. He came back to campus on August 31 to take a second look.[27]

There is little evidence that top University administrators viewed the investigation as cause for alarm. University President Robben W. Fleming and other top administrators had even posed for a photo with Minton when he visited campus. Fleming was coming off an academic year in which he had gained a national reputation for his ability to manage campus anti-war demonstrations and to negotiate a peaceful end to the BAM strike. But over the summer months, campus women were beginning to organize in support of the complaint, and Fleming displayed little sympathy and a certain tone-deafness in his public responses to their concerns.

Credit: Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library, UM News & Information Collection, Box C-18, Human Relations, 8-70, 2040 Folder, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

In a lengthy interview that appeared in the Ann Arbor News the day before the HEW investigators returned to campus Fleming said he was "not alarmed" by the investigation. He said he thought that eradication of sexual discrimination in employment presented more serious problems for enforcement agencies than for employers. "It is clear statistically," he said, "that in professional fields the personnel is overwhelmingly male, and that is the preference of the market." He added, "The question arises whether in a supposedly free economy, market preference should have any weight."

Further, he saw no parallels between BAM's demands and the grievances highlighted by FOCUS. "In the case of blacks, we are talking about opening up educational opportunities, but when it comes to women, we can't say they haven't had equal opportunity. Their complaint lies in being denied access to certain areas of the labor market." (See Document 12.)

Shortly after the complaint was filed, PROBE, a grass-roots organization of campus women, both staff and students, sprung up to support the complaint and to address other University policies that discriminated against women. It included Shortridge, as well as additional faculty members, clerical and blue-collar workers, graduate and undergraduate students. Made up of campus "insiders," it complemented the work of outsiders King and Yourd as it sought to reach out to women at all levels of the university, gather additional information about the discrimination they had encountered, monitor the progress of the HEW complaint and keep the pressure on university administrators to address the issues. It also provided some cover for individual women who wanted to pursue complaints about the sex discrimination they had witnessed or experienced themselves.

An early member recalled that PROBE was just one of many feminist organizations on campus at the time. But the others, she said, "tended to be associated with what was known at that time as the student left-wing radical bra-burning, flaming, anti-establishment movement. PROBE was not quite that radical."

Still, she said, "the deeper any of us got into this the more 'radicalized' we became because it became obvious that there were underlying society problems. . . .We were always meeting and talking. . . . You just realized there was a lot of fundamental problems in society that had to be addressed along with employment discrimination."[28]

One of PROBE's earliest communications to campus women, dated June 16, concluded: "Remember. . . . PROBE's purpose is information gathering. No idea is too far out, too small or too grandiose to be considered for publication or simple availability. Don't let those ideas, anecdotes, or facts die. Send them to PROBE." (See Document 10)

On October 6, 1970, HEW investigator Don Scott wrote Fleming, detailing the systemic discrimination against women that HEW had found in the university's hiring, pay and admissions practices (see Document 13A). Scott said that to remain eligible to receive federal contracts, the University would have to submit a revised affirmative action program within 30 days and commit to stopping its discriminatory practices.

Fleming responded with a brief letter (see Document 13B), in which he contended it would be hard for the University to prepare an affirmative action plan within 30 days, "even assuming we were in complete agreement." He closed by writing, "We do not differ with respect to the principle of equal treatment for women. There are extraordinarily difficult problems in establishing criteria for what constitutes equal treatment, and we believe they are quite different from the now familiar problems in the field of race."

A week later, the University issued a press release (Document 14A), putting a positive spin on the situation. It announced that it was revising its "existing affirmative action plan to promote equal employment opportunities for members of minority groups" to include women, but said it was not likely to meet HEW's 30-day deadline for doing so, and that "some differences are likely between the University and HEW both on what the situation is and what it ought to be." It repeated the words Fleming had used in closing his letter to Scott.[29]

Fleming was recognized for his skills as a labor negotiator and it appears that he believed he could buy time for the University by dialoguing with HEW officials. The president, King recalled, "was up against something he had never been up against before, and stalling was his response."[30] His top female aide, executive assistant Barbara W. Newell, prepared a memo (Document 15), outlining what a response could look like, and what steps might be easy for the University to take. But at the same time, the male administrators who were in charge of the University's personnel policies were aggressively challenging the accuracy of HEW's findings in an internal memo, and urging the administration to fight back (Document 19).

Fleming's presidential papers also demonstrate that even before the news of HEW's findings had been shared with the wider University community, he was distributing them to several other University presidents and lobbyists for associations that represented colleges and universities in Washington (see Documents 16, 17A and 17B). Fleming and his peers felt that they could appeal to top federal officials, including the HEW secretary, to rein in the agency's aggressive regional subordinates. But when word of these contacts and subsequent meetings leaked out, it served only to further infuriate women activists.

The women at Michigan were also helped by a lucky accident of the calendar. The day after the administration announced its response to the HEW findings, a symposium about women on campus was held, part of a long-planned series of events to mark the centennial of the admission of women to Michigan. The events provided an officially sanctioned opportunity to publicize what statistics were available on the relative status of women at the university; for women to focus on ways in which the university had historically—and continued to--discriminate against them; and for women's groups, both formal and informal, to increase their visibility and attract new members.

In August, PROBE had written top University administrators, seeking data to enable it to compare the mean salaries of men and women in the same job categories, as well as the distribution of men and women in each category. Its requests were initially rebuffed, but it gathered what information it could for a 63-page booklet, "The Feminine Mistake: Women at the University of Michigan," that it made available at a teach-in that was part of the celebration.[31] (Two months later, it finally was able to set up a meeting with two officials to discuss getting access to the data it wanted.) (See Document 28).

FOCUS on Equal Employment for Women was among the Ann Arbor women's groups that were included in a directory compiled by the Center for the Continuing Education of Women that was distributed during the centennial celebration, and PROBE was appended to the end of the list. At one of the events, the center's director, Jean Campbell, called for the creation of "an all-University committee, including administrators, members of the faculty, staff and students of varying ages to assess the status of women and women's education at the University of Michigan and to recommend policies or action." Campbell, a more moderate force within the institution, acknowledged to Fleming afterwards that the situation had been complicated by the HEW investigation. But, she added, "It seems to me important to help translate this investigation from its obvious nuisance value to creative concern for women students and employees at the University." (See Document 18)

But the HEW regional office stuck to its guns. Investigator Scott wrote back to Fleming on October 22, advising the president, "Our office does not consider your letter responsive to our findings of deficiencies at your institution." (See Document 13C) More importantly, he noted that HEW had received a request to clear a $400,000 contract with the U.S. Agency for International Development to provide family planning services to the government of Nepal. "No proposed contracts with the University of Michigan will be recommended for clearance until we have specific commitments for overcoming the deficiencies" that had been detailed on October 6.

Scott, King recalled, "was very persistent. He had an independence that Fleming was not used to. And he was a government official. He didn't have to kowtow as a faculty member would have had to. He had the right to those records, and the university wouldn't give them to him."[32] Scott's superior, John Hodgdon, also was determined to take a hard line with the University. The attitudes that he brought to the investigation were reflected in an interview that took place 17 months later (see Document 34).

The support of these particular male civil servants was critical throughout the investigation and in the months beyond. As more and more colleges and universities were the subject of complaints filed by Sandler, WEAL and the National Organization for Women, university presidents and their lobbyists complained that some regional HEW offices were treating universities too harshly. In a memo to members of the Association of American Universities' Council on Federal Relations, its director, Charles Kidd, complained in February 1971 that top HEW officials "realize that the Regional Offices are not staffed with people who understand universities, their hiring procedures, their governance, etc. They both realize that knowledge of these matters is required if the rules relating to discrimination and their administration are to be reasonable. Given the admitted deficiencies of the Regional staff in this area, university officials need not accept without protest rulings, requests for information, etc., which seem unreasonable." (see Document 39B)

The events that fall galvanized women on campus. Fleming's files are filled with a number of heart-felt letters, written by women from across the political spectrum. Mary Maples Dunn, a Bryn Mawr history professor who had just spent a sabbatical year at Michigan, sent a candid letter about what she had observed (see Document 11A). Gloria Gladman, who described herself as "an older student, a conservative and an engineer," referenced Fleming's "public stands" on the HEW report and implored him, "Don't radicalize me and for heaven's sake DON'T INSULT MY INTELLIGENCE with a paternalizing attitude." (see Document 21A) And Marcia Federbush, the wife of a mathematics professor, was among those who were upset that the administration was withholding the HEW findings (see Document 22).

King and Yourd also wrote Fleming, seeking a copy of the HEW response (See Documents 14C and 14D). And in the days before Halloween, another women's group, The Sunday Night Group of the Ann Arbor Women's Liberation Coalition, tacked a flyer on the door of the president's home (Document 20A), threatening to "respond with a trick" if Fleming did not release "the complete and unaltered H.E.W. report" by noon on October 28. Fleming was discomfited enough that he alerted campus security (see Document 20B).

PROBE, meanwhile, decided to try to make use of the University's own mail system to organize campus women. In early November, it prepared a memo (Document 14E) that charged that the University was distributing "misleading" information about the HEW investigation (see Documents 14A and 14B), and encouraged women to come forward with their own stories and offers of support. Letters were addressed to every woman in the U-M staff directory. "I remember sitting around a table, maybe 25 of us, and stuffing envelopes," one member recalled. Several thousand were distributed before the manager of the mail service held up the rest, claiming that the group's use of inter-office mail was "illegal."

"It brought more attention and more involvement, plus it was a lot of fun," the PROBE member recalled. "In a sense it was using the University systems to tweak them a little bit."[33]

King, meanwhile, was continuing to work her own contacts on Capitol Hill. When the complaint was filed "and especially later we felt a lot of support coming unspoken and unwritten through the air from the direction of Washington, DC." (See Document 8). From the staff of Republican U.S. Rep. Garry Brown of Kalamazoo, King learned that a University contract had, in fact, been held up. She enlisted the help of The Michigan Daily, the campus newspaper, to track down the details. On November 6, HEW's 30-day deadline, The Daily broke the story that HEW's Contract Compliance Division had held up what was now described as a $350,000 contract between the U.S. Agency for International Development and the University's Center for Population Planning.

Of the family-planning contract, King recalled: "It was not a happy discovery. We were very glad that the Feds were acting but sad that the contract was for birth control services in Nepal. I am sure the choice was not deliberate (but in our bad moments we were afraid it was). The positive view was that it was probably the first U-M contract that came past after Chicago concluded that Fleming was not going to cooperate with the investigation. Fleming refused to respond to queries, withheld information, and generally interfered with the investigation."[34]

In another interview, King said, "We were kind of disappointed on the topic [of the contract], but we got that into the papers as fast as we could . . . because that was a sign of success, it gave people hope. It didn't give Fleming any hope."[35]

When the news broke, Fleming said of the contract delay: "At the present time the matter is of no concern to us. We are concentrating on the broader question of arriving at an agreement with HEW."[36] On November 3, the University had responded to HEW with proposed amendments to its existing affirmative action plan for minorities and a critique of the HEW findings that followed the lines outlined by University personnel officials in their internal memo (see Document 19). University officials continued to negotiate with HEW over the phone and in person throughout the month.

Douvan, who retained a more favorable view of Fleming than King did, remembered the president's initial response as "'I'm sure we can weather this and it will all go away.' Pretty soon, two weeks later, he was saying, 'Well this is turning out to be a lot tougher than I ever expected,' and so forth. I mean, they held up some millions of dollars worth of contracts, and it was a terrible irony that the first contract held up was in the public health school and it was something that women really supported. But in the long haul, that had to be yielded temporarily in order to make the point that we really wanted to make." (See Document 9)

HEW's action marked the first time a federal contract was withheld specifically to redress findings of campus sex discrimination (as opposed to a university's failure to produce employment data for HEW, as had happened at Harvard earlier in the year.) At the time, the University of Michigan was receiving about $66 million a year in federal contracts, and the revelation signaled that the federal government indeed meant business.

Throughout November, University officials in charge of research activities tried to reassure campus researchers that federal dollars were continuing to flow. On November 25, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research notified the University's Office of Research Administration that five new or continuing Air Force contracts had also been held up because of the ongoing investigation.[37]

In a December 4 article in The Michigan Daily, the University's vice president for research was quoted as saying that most federal agencies were not enthusiastic about having HEW review their contracts. "They're realistic—they don't believe the University of Michigan is any more guilty of sex discrimination than their own agencies. Furthermore, they've got their missions to complete." Still, A. Geoffrey Norman said, "I don't minimize the problem, but, on the other hand, I'm not getting panicked or anything."[38]

But King, for one, thought that was exactly what was happening. Years later, she said, "Knowing what I do about the inside of the university, I [now] realize that between October 27 and the Christmas holiday. . . the faculty member who was applying for a grant would be notified when his grant was not going to come through and he'd complain to his dean and the dean would call Fleming. So I'm sure he sat there with Deans on his neck for weeks. And he had to give in. That was a force he just couldn't deal with."[39]

The University never publicly acknowledged that other contracts had been affected. In mid-December, Muriel Ferris, a legislative aide to Democratic Sen. Philip A. Hart of Michigan, notified King that she had learned that 12 contracts worth less than $1 million each had been held up, as well as a contract for $1.62 million with the Atomic Energy Commission.[40] Various reports later placed the total value of the contracts that were held up at amounts ranging between $3.5 million and $15 million. The University never acknowledged a number higher than the amount of the first contract.

By late November, the events at Michigan were being followed by a nationwide audience. A key article appeared in the November 20 issue of SCIENCE, the magazine of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. It noted that WEAL had filed more than 200 complaints with HEW, and that HEW had held up new contracts at Michigan and "at least three other campuses," which were not identified. "But, Michigan and certain other institutions not identified by HEW officials have chosen to resist. Calling the demands 'totally unreasonable,' Michigan officials circulated copies to several other university administrations in an attempt to gain support." The article noted that campus officials were complaining that the bookwork involved with complying with HEW would be "monumental." But a top compliance official noted that "the requirement for supplying such information is clearly spelled out in each federal contract signed by the universities."[41]

Oral histories conducted with women professors of different ages and from different disciplines who were on campus at the time capture the ways in which the HEW investigation and its aftermath awakened their own feminism and the realization that they had, in fact, been victims of discrimination (see Documents 9, 36 and 37). Sandler said she experienced threatening phone calls and endured confrontations at professional conferences, but other men were supportive. "Remember a lot of academics are married to other academics or people who wanted to be academics. I don't know what the numbers are, but certainly there are some men who were married to women who were professionals or aspiring professionals and some of them knew what had happened to their wives. And you had some men who had daughters, so there were always some people who were sympathetic, but there were also lots of people who felt this was a lot of nonsense."[42] Certainly on the Michigan campus, those kinds of negative views can be found in documents that were circulated internally as the controversy unfolded (see Documents 19 and 27).

On December 4, Scott notified Fleming that neither subsequent letters nor meetings with HEW officials "were considered an adequate response to our letter of findings. Until the University of Michigan has committed itself to overcoming the deficiencies in the letter outlining our findings this office will not be in position to clear the award of further Federal contracts." Scott said that if the University did not respond within 15 days, the Chicago office would recommend that its Washington office initiate "formal enforcement proceedings."[43] Scott followed up the next day with a telegram detailing the key points, excerpts of which the University eventually released (see Document 23).

At that point, Fleming decided he had to act and his papers reflect a change in his sense of urgency. As he headed out of town, he set out a proposed response to the rest of the executive officers and his reasoning (see Document 24). The next day, he sent a carefully crafted letter to Scott (see Document 25). The University still rejected the assertion that HEW had any jurisdiction over graduate school admissions, and he attached a copy of the telegram that he was sending the same day to Scott's ultimate superior, HEW Secretary Elliot L. Richardson (see Document 26).

In the telegram, Fleming said that it would be "unworkable" for the University to increase the number of women faculty to reflect their share of the pool of potential applicants, presumably the percentage of women holding doctorates in a particular field. He added that he was confident that Richardson did not want to use "the contract compliance device to coerce universities into signing agreements on matters of profound significance" without reviewing the matter with his top officials. Further, Fleming threatened that "some research and service activities in support of federal programs will be impaired within the next few days" if HEW did not lift its "embargo" on contracts.

While Fleming was still using back-door channels to challenge HEW's Chicago regional office, the University finally released excerpts of Scott's original findings (Document 13A) and excerpts of its latest response (Document 25), demonstrating how it was addressing each of the original HEW requirements. The response indicated that it still disagreed with HEW over graduate admissions and how far back it had to go to correct any instances of pay inequity that were identified. But the University did not share with the public the portion of the letter to Scott that said it was going to continue to pursue its fight to Secretary Richardson.

Although HEW had still not accepted the University's plans, the University scored a bit of a public relations victory. The Detroit Free Press reported that the University "appears to have the lead on all other universities in its attempts to eliminate effects of discrimination against women staff. While spokesmen for major universities across the country emphasized a growing awareness of sex discrimination on the campus and work underway to correct discriminatory practices, only Michigan had publicly announced concrete steps it will take to correct such practices."[44]

Rose Vainstein, a professor of library science, was among those who were interviewed by HEW investigators during these years. She recalled that they seemed disappointed when she said she had not personally experienced discrimination "because nobody in library science at that time was paid a decent salary, and I was not being paid any lower salary than anybody else." But, she added, "I think that the pressure that was coming nationally was very important, and it was coming particularly, I think, on prestigious universities like Michigan because I think [HEW] had a feeling that if they could show discriminatory practices at a place like Michigan then everybody else would fall in line. . . . But there's no doubt when you looked at the overall numbers that there were so few female appointments at the University that there was a hidden agenda from way back when, when appointments were made."[45]

As part of its settlement, the University also said it would create a Commission on Women, something HEW had never actually pushed it to do. In mid-December, Fleming told his executive team how this would be done (see Document 29). Almost immediately, the commission itself became controversial when Barbara Newell, Fleming's aide, was installed as chairman. Activist women who were not included in the process viewed the commission as just another University ploy for managing the crisis and generating favorable public relations. Still, the new commission became a model for other universities and for the first time gave campus women an institutionalized focal point for airing their concerns (see Document 33).

As the holiday break approached, the University still sought a definitive agreement from HEW that no more contracts would be delayed. Phone calls and telegrams flew back and forth between Ann Arbor and Washington. On December 21, Allan F. Smith, vice president for academic affairs, and several other University officials held a 2 ½ hour meeting with J. Stanley Pottinger, director of HEW's Office of Civil Rights in Washington. The University still did not concede that HEW had jurisdiction over discrimination in graduate admissions, but by now it said it was prepared to comply if Secretary Richardson backed up his subordinates.[46]

On Christmas Eve, Pottinger wrote Fleming, outlining his view of the terms of the agreement. HEW would still require the University to adopt goals and timetables for hiring more female faculty members, but would await Richardson's decision on graduate admissions. However, he also asserted that HEW expected the University to review its files to achieve salary equity among men and women with similar experience and responsibilities, and to create a complaint procedure for women who felt their salaries should be reviewed, without them having to produce the supporting evidence.

"Upon receipt of your written concurrence," Pottinger said, HEW would consider the University in compliance with the executive orders "for purposes of contract clearance. However," Pottinger added, "we would not be precluded from reimposing controls upon contract clearances should the agreements . . . not be faithfully kept or should other evidence of non-compliance come to our attention."[47]

Fleming provided that letter on the last day of 1970.[48]

In the new year, Owen P. Kiely, HEW's director of contract compliance, who had participated in the meetings with Pottinger, described the agreement with Michigan as "historic." The University, he said, "could be a model to the extent that other institutions have these kinds of problems," Kiely said. The official said that at the time, 16 other colleges and the 13 schools in the Georgia state college system were "targets of HEW investigations." Sandler responded, "It's a beginning. But we've got a long way to go yet, baby."[49]

The University still had to scramble to make good on all of its pledges to HEW by the 90-day deadline on March 6. In mid-January, the first members of the new Commission on Women were announced, but Fleming made clear to the University's executive officers that he was going to proceed without actually getting any input from them (see Document 30). At the same time, he was continuing to work with other university presidents to persuade Richardson not to impose requirements on graduate admissions (see Document 31).[50]

The underlying irony was captured in another long article that appeared in The Michigan Daily, less than a year after Kathleen Shortridge's article (see Document 6) had defined the problem. "It's true the University is the first college in the country to tackle the problem of sex discrimination," senior editor Daniel Zwerdling wrote. "It sounds so glorious! One begins to forget the University started the discrimination in the first place. But behind administrative doors, the men of the University are grumbling." Zwerdling captured unguarded quotations from several top administrators, including those who were directly involved with implementing the affirmative action plan (see Document 32).

HEW officials continued to wrangle with the University over its affirmative action plan for the next few years (see Document 34). But slowly, change was happening. The Commission on Women began to become an institutional advocate for women on campus as its original membership was expanded, its members learned more about the extent of discrimination, and they began to find their own voices (see Documents 33 and 36). At least 100 women staff members were given raises totaling $94,295 as a result of the complaint, including Douvan, whose salary was more than doubled. Still she was not compensated for the years she had worked before the executive order was issued, or for the future pension benefits she had lost (see Document 9).[51]

The members of PROBE, meanwhile, continued to look for creative ways to highlight the problems that campus women faced. In April 1972, a sub-group, calling themselves The Ad Hoc Committee Concerned that President Fleming Does Not Meet with Enough Women (AHCCTPFDNMEW),[52] organized what it called "The Fleming Follow," during which the women sat outside Fleming's office for a week, compiling details of who got an audience with the president. They found that of the 145 persons he had met with, only 21 were women, and all but one of them were part of a group. Jean King, they reported with pride, "feels that [the initiative] has the potential to be a national classic." Fleming, for his part, subsequently met with the members several times to discuss the underlying issues. In thanking him, coordinator Jeanne Tashian said the discussions "have been generally worthwhile, somewhat productive, basically non-adversarial, in fact friendly." (See Documents 35A to 35D).

As King's comment indicated, more and more women around the country were looking to the women of Michigan for help in pursuing complaints against their own universities. King and Sandler continued to cultivate their media contacts to help spread the word. King observed that "the reporters are like the women that were working for Congress, they were underpaid, they were angry, and they won these cases." She added, "We deliberately used the Chronicle (for [sic] Higher Education), because that would get it out to every faculty member in the United States."[53]

In March 1971, Cheryl M. Fields wrote a front-page article for the Chronicle of Higher Education about the growing number of investigations. "Sex discrimination—and government and university efforts to get rid of it—has emerged in the past year as one of the most controversial and sensitive issues on the nation's campuses. While not as well-publicized as student unrest, federal investigations of whether women have been discriminated against in hiring, pay, and promotions at colleges and universities have challenged many institutions' self images and long-established policies and operating procedures."

Michigan, she noted, had promised to pay back wages to women who had suffered discrimination; projected that it would increase the number of women on the instructional staff by 33 percent by the 1973-74 academic year; promised to achieve salary equity between men and women in the same job categories who had equivalent qualifications, responsibilities and performance; and liberalized its anti-nepotism policies. Fields reported that HEW had initiated at least 40 investigations and quoted an unidentified HEW official as saying that contracts had been held up at a dozen more colleges.[54]

Throughout 1970, Sandler had continued to coach women from dozens of universities on how to file complaints. She was joined by Ann Scott, an English professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, who served as federal compliance coordinator for the National Organization for Women. Scott prepared a "kit" that explained the presidential executive order and provided easy-to-follow instructions on how to file a complaint (see Document 38).

Scott was among the feminists that PROBE invited to speak on campus in the spring of 1971. One of them, Mary Jean Collins-Robson, NOW's Midwest regional director, "reported that as a result of the HEW investigation of the U. of M., Ann Arbor is regarded as a Midwestern feminist mecca," according to a PROBE newsletter later that year. "OK, women," it urged its membership, "let's live up to that reputation." (See Document 41) Women who had pursued action against their university employers as individuals also reached out to PROBE leaders for support (see Document 40).

Sandler recalled how ill prepared HEW and the Labor Department had been to deal with the volume of complaints that were generated because most of its investigators were males who had previously focused on racial discrimination. She said that she and Ann Scott frequently met with top agency officials to advise them on how to investigate the complaints. "At the same time higher education is getting a little nervous," she recalled. "They realize at this point there is a series of complaints. It is not just the complaint against the University of Michigan, it's not just a complaint against Harvard, but now we have over 100, and the numbers are rising." By the summer of 1970, "it was close to maybe 200 or something like that. So higher education is astonished. Here comes these investigators from the government saying 'We want data and we want to tell you what to do' essentially, and they were stunned."[55]

In the year and a half after the Michigan complaint was filed, the Labor Department's Office of Federal Contract Compliance slowly developed guidelines explaining how educational institutions were expected to comply with the rules barring sex discrimination by federal contractors. In December 1971, it released a new set of rules, known as "Revised Order Number 4," describing its expectations for affirmative action plans. By this point, HEW still had not given final approval to Michigan's goals and timetables, and these rules set off another howl of opposition from Fleming, his academic allies and more conservative academics.

Their argument was that the government was ordering them to hire women and minorities, as long as they were more qualified than the least qualified person currently employed by a department. In a Detroit News story headlined, "HEW Cuts Faculty Quality, Colleges Fear," an unidentified Michigan official complained that the rule could not be applied "without seriously diluting the quality of teaching." Another administrator said, "If HEW is really serious about enforcing that requirement, it would be disastrous. You can imagine the havoc it would wreak in the Department of Surgery, for instance." (see Document 42)

Sidney Hook, a professor of philosophy at New York University, was among those who publicly challenged HEW's statistical approach to identifying sex discrimination: "They have completely disregarded the all-important criterion of qualifications or requisite skills, and assumed that what may be a legitimate inference in considering the presence or absence of discrimination in hiring individuals for an assembly line. . . holds for all levels of university instruction."

But Pottinger and Hodgdon continued to hold firm. "This has been necessary," Pottinger responded, "because of years of neglect by the universities. But I don't think this constitutes a quota system." (see also Document 34).

In March 1973, staff members of the Office of Civil Rights once again advised the University of Michigan that its amended affirmative action plan was still "deficient." The agency required "a detailed response to these findings, including specific actions to be taken and timetables for implementing each commitment." The agency again set a deadline by which the University was expected to respond.[56]

And once again, Jean King fired off another round of letters to members of Congress. This time she thanked U.S. Rep Martha Griffiths, the Michigan Democrat, for the support she had provided since the original complaint was first filed. "We are certain that this matter would never have come to the stage it has reached if it had not been for the 'Congressionals' which you issued on our behalf."

Since then, the number of women serving in the U.S. House had grown by nearly 50 percent, and this time, King wrote 14 other female members. The office of one of them, Democratic Rep. Barbara Jordan of Texas, replied that Jordan viewed the issue as a Michigan matter. But King begged to disagree. "Women all over the United States await developments at the University of Michigan in order to gauge the chances of success in their own local efforts. The effectiveness or lack thereof which the HEW shows vis-à-vis the University of Michigan will be critical in determining whether HEW indeed has any clout at all in enforcing compliance in other educational institutions, including colleges and universities in Texas." (See Documents 43A-43D)

Ruth Galvin, who had interviewed King for a March 12, 1973 article, headlined "Battle of Ann Arbor," in "The Sexes" section of Time magazine, wrote her a few weeks before the article appeared: "Senator [Philip] Hart's office feels, by the way, that so long as people like you persist in asking questions, HEW cannot desist regardless of money shortages. They feel the Columbia [University] case needs someone like you. Do you know if there is a 'Jean King' involved in the Columbia fight?"[57]

As the months went by, political tides shifted and the federal government retreated from the aggressive role it had once played in enforcing the executive order. While longtime male (and increasingly female) civil servants took the lead in challenging the universities' practices, their priorities were ultimately set by the political superiors to whom they reported. Reviewing the totality of the Nixon administration's efforts on addressing sex discrimination, historian Dean J. Kotlowski wrote, "[O]n women's rights, the president and his aides were too steeped in traditional roles to offer anything beyond halfhearted leadership. The result was more action on women's rights than in previous administrations, but also a series of stops and starts on the path to gender equality."[58]

Douvan recalled in 1999, near the end of the Clinton administration:

"[T]hat was an exciting time and I think was critical in bringing about some of the changes. Now in subsequent administrations in Washington, I think that the [Equal Employment Opportunity Commission] has been so watered down that I'm not sure they would have held up the contracts today. . . .So it was a luck issue partly, a luck of timing." (See Document 9)

Still by 1973, the genie was out of the bottle. Sandler's early work led Edith Green of Oregon, Democratic chair of the House Education and Labor subcommittee on higher education, to hold hearings in the summer of 1970 on sex discrimination in higher education. Sandler played a key role in organizing the hearings and compiling a two-volume record of the proceedings that was printed in bulk and distributed nationwide. The following year, a number of bills were introduced in Congress that sought to end sex discrimination in education. Finally, in July 1972, Congress amended the Equal Pay Act of 1963 to include executive, administrative and professional employees. It also passed what became known as "Title IX" of the Education Act Amendments of 1972, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex in educational institutions that received federal funding. The laws that faculty members and women students had needed to pursue discrimination were finally on the books. The climate at universities like Michigan slowly began to change, as many created offices focused on recruiting and hiring more women and minorities, as well as other disadvantaged groups, such as disabled students and veterans.

On the Michigan campus, women remembered the days of the HEW investigation in different ways. Ann Larimore, a geography professor who was the first woman elected to the executive board of the University's Rackham Graduate School, said, "I've always thought that we were very, very fortunate on this campus to have President Fleming at the helm at that time. He was one of the major reasons why all those turbulent years at the University of Michigan were largely, if not almost entirely, non-violent." Larimore recalled how at some point she realized that she had been given a secretary's desk in her department. "But in a couple of years I had an office of my own and always got the office I wanted from then on, so that worked itself out very quickly." (See Document 37)

Harriet Mills, a professor of Chinese who was one of the first members of the Commission on Women, recalled that Fleming "was very supportive. Not coming out here on the sidelines and rah-rahing, but in his wisdom and decency there was an element of sort of you had to respect him. And we look back with great fondness on that."[59] Douvan, one of the members of FOCUS, said, "[C]ertainly Robben Fleming has done a lot for women." (See Document 9)

But King remained angry about Fleming's response to the complaint, particularly after he made no mention of the episode in his 1996 autobiography, Tempest into Rainbows: Managing Turbulence, in which he reflected on the way he had handled anti-war protests and the BAM strike.

In an interview in 2001, she attributed this to the fact that Fleming "got beaten! On his own territory! He was a labor negotiator, and he was up against somebody that he couldn't negotiate with. . . . What is he supposed to say? Not only was he angry and stubborn and refused to respond, but I think he organized other universities, and I think he had the university attorney organize the other attorneys. He still to this day regards us as very unfair."[60]

Sandler observed that Fleming could have turned the episode into more of a public relations advantage in his book by claiming credit for creating the Commission on Women. "But like many men," she noted, his attitude was "these are like gnats bothering me. He saw it as a bunch of women making him and the university uncomfortable. . . . It was just not that important to him."[61]

Seven years after they first worked together on the complaint, Sandler wrote King, responding to advice she had given to a woman who was planning to file a lawsuit alleging sex discrimination: "Your advice was right on target; the problem for many of these women is partially not knowing how the system operates. Of course, many men don't know how the system operates either, but then they don't need to know since it operates to their benefit with or without their awareness. In contrast, the only way women can effectively operate within it is to know it for what it is, and in a sense, beat the system as its own game."

But Sandler noted ruefully that judges were still reluctant to interfere in academic cases, no matter what the law now said. She added, "It is going to take a long, long time."[62]

Still, by the 2008-09 academic year, American women did achieve a milestone that was a long time coming: for the first time they earned a majority of the doctoral degrees awarded by U.S. universities. For many years, women had outnumbered men when it came to earning bachelor's and master's degrees. But, as one newspaper noted, "women who aspired to become college professors, a common path for those with doctorates, were hindered by the particular demands of faculty life. Studies have found that the tenure clock often collides with the biological clock: The busiest years of the academic career are the years that well-educated women tend to have children."[63]

Over the four decades since the women at the University of Michigan pursued their complaint, the university evolved into a leading proponent of the use of affirmative action to help achieve diversity in student admissions, defending that approach all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In late 2012, the University of Michigan was led by a woman, and was governed by a Board of Regents on which women were in the majority. But women still had not achieved full parity in academic hiring or salaries—a trend that was also seen nationwide. Fully tenured male professors at U-M still made roughly $14,400 more a year than female professors, while female assistant professors earned an average of $6,100 less. "I think it's closing," Reuven Avi-Yonah, a law professor who chaired the Tenure, Promotions and Professional Development Committee, said of the pay gap. "It's just a question of seniority. We have many more younger women faculty (than we used to)."[64]

King knew that women would continue to face hurdles in challenging discrimination in higher education. In 1999, she observed:

". . . Certainly numbers have improved. . . .Scholarships have improved. Admissions have improved. Faculty has improved. . . .The number of faculty have improved. They are not what they ought to be, but they started with nothing. . . .

That's the reason that this administrative complaint was necessary. We'd still be there if there hadn't been something to do. And . . . it didn't create a great change, it didn't. I mean, we wanted all those things fixed immediately in five minutes. And they appointed committees and they did studies and they interviewed people and they wrote reports. And the stuff was just obvious."[65]

Jean King was overly modest in these remarks almost thirty years after she pursued her complaint about sex discrimination at the University of Michigan. King and the others who pressed the University and HEW launched a new wave of affirmative action on behalf of women that played a major role in the transformation of women's place in higher education in the United States over succeeding decades.