Document 9A: Harriet Beecher Stowe to Mrs. Cowles, 4 August 1852, Henry Cowles Papers, Box #3, Series: Correspondence, Personal; Folders: Aug-Dec 1852 and Jan-July 1853; Record Group 30/27, Oberlin College Archives.

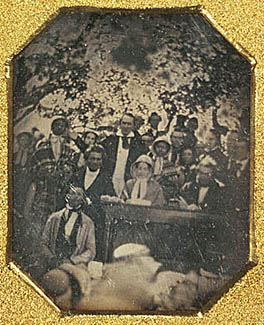

The 1850 Fugitive

Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York. The Edmonson

sisters are standing wearing bonnets and shawls in the row behind the

seated speakers. Frederick Douglass is seated, with Gerritt Smith standing

behind him, and with Abby Kelley Foster the likely person seated on Douglass's

left.

Ezra Greenleaf Weld, Daguerreotype, Mat: 3 3/16 x 2 3/4 in., 84.XT.1582.5.

Introduction

Mary and Emily Edmondson were among fourteen siblings born into slavery in Washington, D.C., to a free African-American father and an enslaved mother. In 1848, these sisters, their brothers Samuel and Richard, and 73 others attempted to flee to freedom on the schooner Pearl. The ship was recaptured, and the girls were taken by a trader to the New Orleans slave pens to be sold as "fancy girls." Paul Edmondson, the girls' father, went to New York to plead their case with the New York Anti-Slavery Society, and, more successfully, with Reverend Henry Ward Beecher and his Brooklyn church, which raised the money to buy the girls out of slavery. The case caught the attention of Beecher's sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, then completing Uncle Tom's Cabin. She decided to take responsibility for the girls' educations. With the hopes of becoming missionaries teaching American blacks who had settled in Canada, Emily and Mary enrolled in Oberlin's Preparatory Department in 1852. Tragically, Mary had become infected with pulmonary consumption before gaining her freedom, and grew progressively weaker throughout her first year at Oberlin. She died on May 18, 1853. Emily returned to Washington, where she assisted in Myrtilla Miner's[16] school for African-American girls until she married. In the first two letters of this series, Harriet Beecher Stowe writes to Mrs. Cowles, with whom the sisters lived while students at Oberlin, and Mary Edmondson, (see Document 9B) discussing payments for the girls' education, and displaying genuine engagement in the academic progress of the girls. The third letter, written by Emily Edmondson to the Cowles family after her sister's death and her own return to Washington, emphasizes the close connections she formed with the Cowles family and the Oberlin community as well as her grief over Mary's death (see Document 9C). The document indicates as well, Emily's religious fervor and continued involvement with the anti-slavery movement. Emily would later go to the deep South to buy her brother out of slavery on Frederick Douglass's sponsorship.

Brunswick August 4.Dear Mrs. Cowles

Last week I wrote to Mrs. Finney[A], not having then heard from you, I am now quite comforted on my return at the favorable aspect of your letter. I am glad that God inclines your hearts to these girls. & I trust that your efforts for them will be crowned with success.

I enclose you herewith a check for 20 which with the $30 I sent will make 50 & if it is thought best all round among you there, you may buy two scholarships with it so that when these two have been educated there two others may succeed them. I foresee an opening in this way to accomplish much good. Twenty five dollars of this money was given by the sewing society of the Salem St. Church Br Edward Beecher minister[B] & the scholarship may stand in their name. The other may stand in mine.

In regard to Mary's spinal difficulty I think if she will wear a wet bandage over the part affected after the manner of the water cure, bathe daily in cold water & take at least one good regular walk in the open air every day that she will find herself getting better. I notice already the improvement in Emily's last letter as to spelling. Tell her to write rather large and form every letter distinctly. Young writers often think that writing a small hand makes their writing look better but they are mistaken. When they have learned to write a large clear hand they may run it out as badly as I to who have two dozen letters to write. I want to get a letter from Mary.

I have not time to write much. I hope one of the girls will acknowledge the receipt of the money the $30 check was sent about two weeks since. I have not got a definite answer from their mother yet.

I wish I could come to Oberlin this fall. Nothing but the absolute impossibility of being in four or five places at once prevents me. In other words I am fast bound to my family as we have to move to Andover this fall and get a house fitted up with many et coeteras. You will appreciate this reason but I am coming sometime.

Yours very affectionately[signed] H.B. Stowe

P. S. I shall soon forward some ready money for you to have on hand for books clothing & other expenses. There will I trust be no difficulty in meeting all claims your statements struck me as very fair & reasonable.

A. Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), corresponded primarily with Oberlin women, rather than the men who held official positions in the College.

Back To TextB. Edward Beecher (1803-1895), Harriet Beecher Stowe's brother, was an abolitionist, then pastor of Boston's Salem Street Church.

Back To Text